Medication Safety Checker for Lung Health

Check Your Medication Safety

Identify medications that may cause lung scarring and learn about monitoring recommendations

Enter a medication name to check risk for pulmonary fibrosis.

Most people assume that if a doctor prescribes a medication, it’s safe. But some drugs quietly scar your lungs over time - without warning, without pain, until you can’t catch your breath. This isn’t rare. It’s drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis, a condition where medicines turn healthy lung tissue into stiff, scarred tissue. And it’s happening more than you think.

What Exactly Is Drug-Induced Pulmonary Fibrosis?

Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis (DIPF) is a type of lung scarring caused by certain medications. Your lungs are made of tiny air sacs called alveoli, surrounded by thin walls that let oxygen into your blood. When these walls get damaged by a drug, your body tries to heal them - but instead of normal tissue, it builds thick, fibrous scar tissue. That’s fibrosis. And once it’s there, it doesn’t go away.

Unlike infections or asthma, DIPF doesn’t come with a fever or wheezing. It starts slow. You might notice you’re getting winded faster than usual during a walk, or you’re coughing more - a dry, nagging cough that won’t quit. At first, you blame it on aging, on being out of shape, on allergies. But if you’re taking one of the high-risk drugs, it could be something far more serious.

Which Medications Are Most Likely to Cause It?

Over 50 medications have been linked to pulmonary fibrosis. But just three account for nearly half of all reported cases:

- Nitrofurantoin - a common antibiotic for urinary tract infections. Used for years as a preventive, it’s especially dangerous in older adults. Cases have shown up after just six months of use - or after ten years.

- Methotrexate - used for rheumatoid arthritis, psoriasis, and some cancers. About 1 in 20 people on long-term methotrexate develop lung damage. It can strike suddenly, turning into acute pneumonia within weeks.

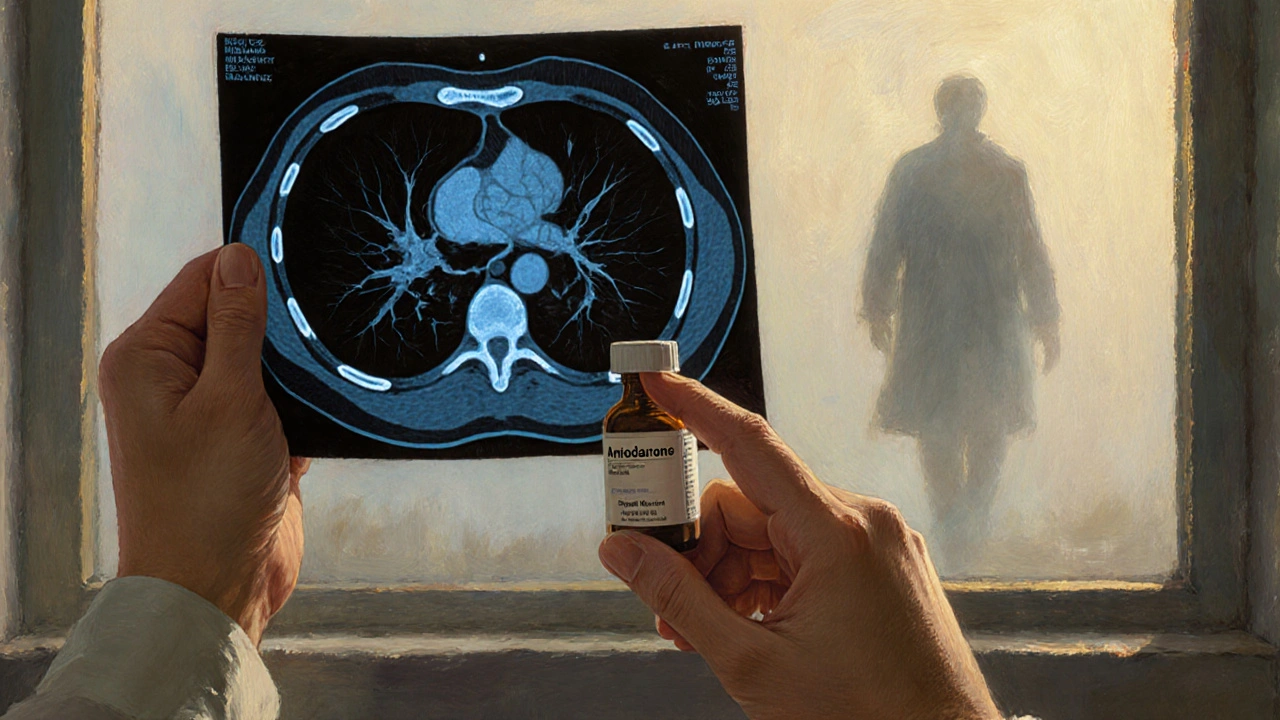

- Amiodarone - a heart rhythm drug. Even though it’s lifesaving for arrhythmias, 5 to 7% of people who take it for more than six months develop lung scarring. The risk climbs with higher doses and longer use.

Chemotherapy drugs are another major culprit. Bleomycin, used for testicular cancer and lymphoma, causes lung damage in up to 20% of patients. Cyclophosphamide and other chemo agents aren’t far behind. Even newer cancer treatments - immune checkpoint inhibitors like Keytruda and Opdivo - have been tied to sudden, severe lung inflammation that can turn into fibrosis.

Other offenders include:

- Sulfa antibiotics

- Penicillamine (for rheumatoid arthritis)

- Gold salts (older arthritis treatment)

- Some heart medications like propranolol and hydralazine

- Anti-inflammatory drugs like dasatinib and nilotinib

The scary part? There’s no safe dose. One person takes amiodarone for five years and stays fine. Another takes it for six months and ends up on oxygen. Why? We don’t know. It’s unpredictable. Genetics, age, existing lung conditions - they all play a role, but no one can say who’s at risk before it happens.

How Do You Know If It’s Happening to You?

The symptoms are vague. That’s why so many cases are missed.

- A dry cough that won’t go away - not from a cold, not from post-nasal drip, just persistent.

- Shortness of breath during normal activities - climbing stairs, carrying groceries, walking to the mailbox.

- Unexplained fatigue - not just tired, but drained even after sleeping.

- Crackling sounds in your lungs when your doctor listens - like Velcro being pulled apart.

- Clubbing of fingers - the tips of your fingers become rounded and the nails curve down.

Studies show that 78% of people with drug-induced fibrosis report worsening breathlessness. 65% have a chronic cough. 32% get fevers, joint pain, or weight loss. These aren’t side effects you brush off. They’re red flags.

And here’s the catch: chest X-rays often look normal early on. You need a high-resolution CT scan to see the scarring. And even then, doctors have to rule out other causes - like autoimmune disease, asbestos exposure, or idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF). That’s why a full drug history is critical. If you’ve been on any of these meds for months or years, your doctor needs to know.

What Happens After Diagnosis?

There’s no magic pill to reverse the scarring. But stopping the drug is the single most effective treatment.

According to data from the Action Pulmonary Fibrosis organization, 89% of patients who stop the offending medication see improvement within three months. Some recover nearly all their lung function. Others are left with permanent damage - but at least it doesn’t get worse.

For those with moderate to severe symptoms, doctors often prescribe high-dose steroids like prednisone. The goal is to calm the inflammation before it turns to scar tissue. Treatment usually lasts 3 to 6 months, with slow tapering to avoid rebound effects.

Oxygen therapy helps if your blood oxygen drops below 88%. Pulmonary rehab - breathing exercises, light exercise training - can improve quality of life. Regular lung function tests every 3 to 6 months track progress.

But here’s the hard truth: if you wait too long, the damage is irreversible. The average time from symptom onset to diagnosis is over eight weeks. By then, many patients have already lost significant lung capacity.

Why Is This Underdiagnosed?

In a 2022 survey, only 58% of primary care doctors routinely asked patients on high-risk drugs about breathing problems. Most assume the symptoms are normal aging. Or they blame it on COPD, asthma, or heart failure.

Patients don’t always connect the dots either. They don’t think their arthritis pill or UTI antibiotic could hurt their lungs. And when they do mention a cough, doctors often don’t dig deeper.

Even worse - some drugs aren’t even labeled with this risk. Amiodarone’s warning about lung damage is buried in the fine print. Nitrofurantoin’s label doesn’t clearly state it can cause fibrosis in long-term users. Regulatory agencies like Medsafe in New Zealand have had to issue direct alerts because the warnings aren’t enough.

Who’s Most at Risk?

It’s not just the elderly - though they’re most commonly affected. Risk factors include:

- Age over 60

- Long-term use of the drug (months to years)

- High cumulative dose - especially with amiodarone (over 400 grams total)

- Pre-existing lung disease like COPD or asthma

- History of radiation to the chest

- Genetic susceptibility - though we can’t test for it yet

Women are slightly more likely to develop methotrexate-induced lung injury. People with rheumatoid arthritis on methotrexate are at higher risk than those taking it for cancer.

The bottom line? If you’ve been on any of these drugs for more than six months - especially nitrofurantoin, amiodarone, or methotrexate - and you’ve noticed any breathing changes, talk to your doctor. Don’t wait for a crisis.

What Can You Do to Protect Yourself?

Knowledge is your best defense.

- Ask your doctor before starting any new medication: “Can this cause lung damage?”

- Know your meds. Keep a list of everything you take - including over-the-counter drugs and supplements.

- Report symptoms early. If you get a dry cough, shortness of breath, or unexplained fatigue, don’t ignore it. Say: “I’m on [drug name]. Could this be related?”

- Request a baseline lung test. If you’re starting amiodarone or methotrexate, ask for a pulmonary function test (PFT) before you begin. Repeat it every 6 to 12 months.

- Don’t stop meds on your own. If you suspect a problem, see your doctor. Stopping suddenly can be dangerous with heart or cancer drugs.

There’s no cure for pulmonary fibrosis - but early action can stop it from getting worse. And in many cases, it can reverse.

What’s Next for This Problem?

Researchers are working on ways to predict who’s at risk. Blood tests for biomarkers, genetic screening, and AI analysis of CT scans are all in early trials. The goal? To catch lung damage before it becomes scarring.

Regulators are catching up too. New Zealand’s Medsafe updated its guidelines in December 2024 to remind doctors to warn patients. The European Respiratory Society now recommends baseline lung testing before starting high-risk drugs.

But until we have better tools, vigilance is the only protection.

Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis isn’t a myth. It’s real. It’s growing. And it’s silent - until it’s too late. If you’re on one of these medications, don’t wait for your lungs to give out. Ask the question now. Protect yourself before the scar tissue forms.

Can you get pulmonary fibrosis from a short course of antibiotics like nitrofurantoin?

Yes. While nitrofurantoin is most often linked to long-term use - like months or years for UTI prevention - cases have been documented after just six weeks. It’s unpredictable. Even a single course can trigger a reaction in rare cases, especially in older adults or those with existing lung conditions.

Is drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis the same as idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis (IPF)?

No. Idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis has no known cause and typically progresses slowly over years. Drug-induced pulmonary fibrosis is caused by a specific medication and may stop progressing - or even improve - if the drug is stopped early. The lung scarring looks similar on scans, but the cause and potential for recovery are different.

Can steroids reverse lung scarring from drugs?

Steroids like prednisone can’t undo scar tissue, but they can stop ongoing inflammation that leads to more scarring. If caught early, steroids can help preserve lung function and even allow some healing. But if the fibrosis is advanced, steroids won’t reverse it - only stopping the drug can prevent further damage.

Are newer cancer drugs like immunotherapy safer for the lungs?

No. Immune checkpoint inhibitors like pembrolizumab and nivolumab are among the fastest-growing causes of drug-induced lung injury. They can cause severe inflammation within weeks of starting treatment. This isn’t a side effect - it’s an immune attack on the lungs. Doctors now monitor patients closely with CT scans and lung function tests during treatment.

How often should I get my lungs checked if I’m on amiodarone or methotrexate?

If you’re on amiodarone, get a baseline pulmonary function test before starting, then every 6 to 12 months. For methotrexate, especially if you have rheumatoid arthritis, get checked every 6 months. If you develop any cough or shortness of breath, get a high-resolution CT scan immediately - don’t wait for your next scheduled test.

Comments(13)