When the liver can’t do its job, blood sugar often goes off‑track. Liver Failure is a severe loss of liver function that can stem from chronic disease, toxins, or acute injury. It disrupts metabolism, hormone balance, and detoxification, setting the stage for a cascade of problems-including Diabetes Mellitus a chronic condition marked by high blood glucose and impaired insulin action. Understanding liver failure and diabetes isn’t just trivia; it can shape screening, treatment, and lifestyle choices for millions.

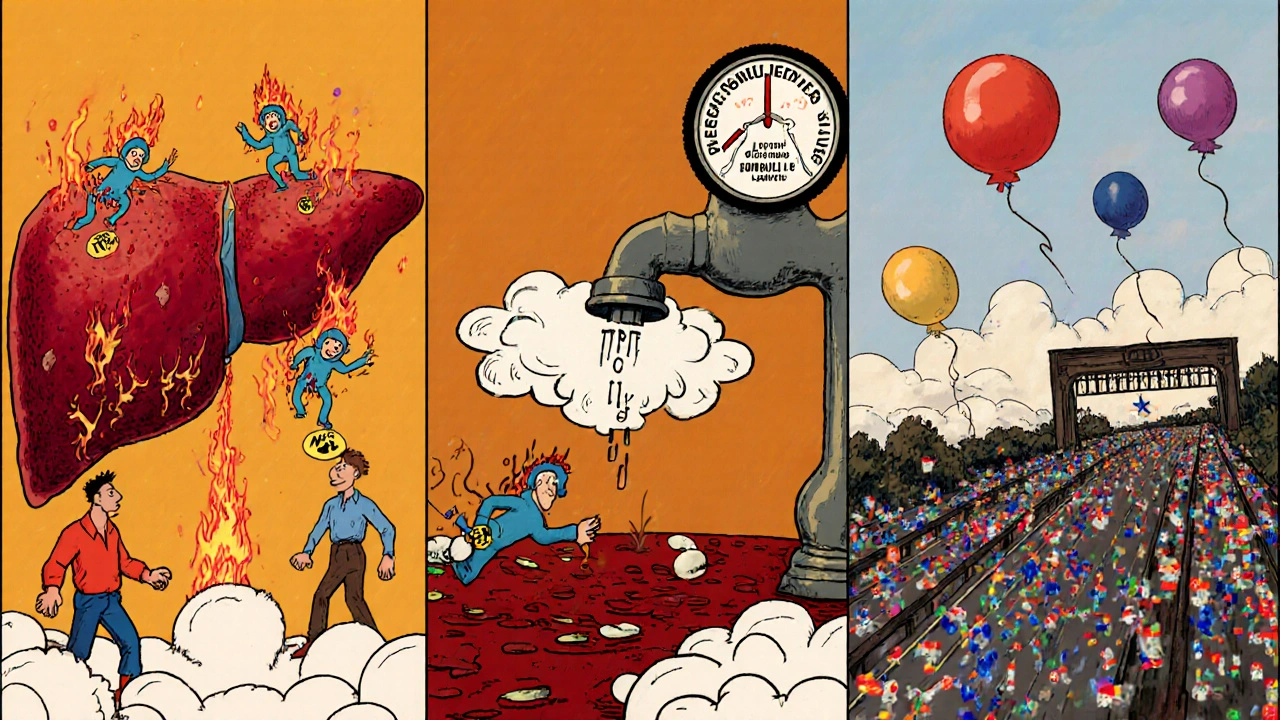

Why Liver Failure Fuels Diabetes

The liver is the body’s sugar‑regulating hub. It stores glucose as glycogen, releases it during fasting, and clears excess glucose after meals. When liver cells are damaged, three key mechanisms tip the balance toward diabetes:

- Insulin resistance: Damaged liver tissue releases inflammatory cytokines (TNF‑α, IL‑6) that blunt insulin signaling in muscle and fat. This is the same resistance seen in Non‑alcoholic fatty liver disease (NAFLD), a common precursor to both cirrhosis and type 2 diabetes.

- Impaired gluconeogenesis control: A healthy liver knows when to stop making glucose. Failing hepatocytes lose that brake, pumping out glucose even when blood levels are already high.

- Hormonal disruption: The liver clears excess insulin and regulates glucagon. Failure leads to hyperinsulinemia, which paradoxically worsens insulin resistance.

These shifts don’t happen overnight. Studies from 2023‑2024 show that patients with advanced fibrosis have a 2‑3× higher odds of developing type 2 diabetes within five years.

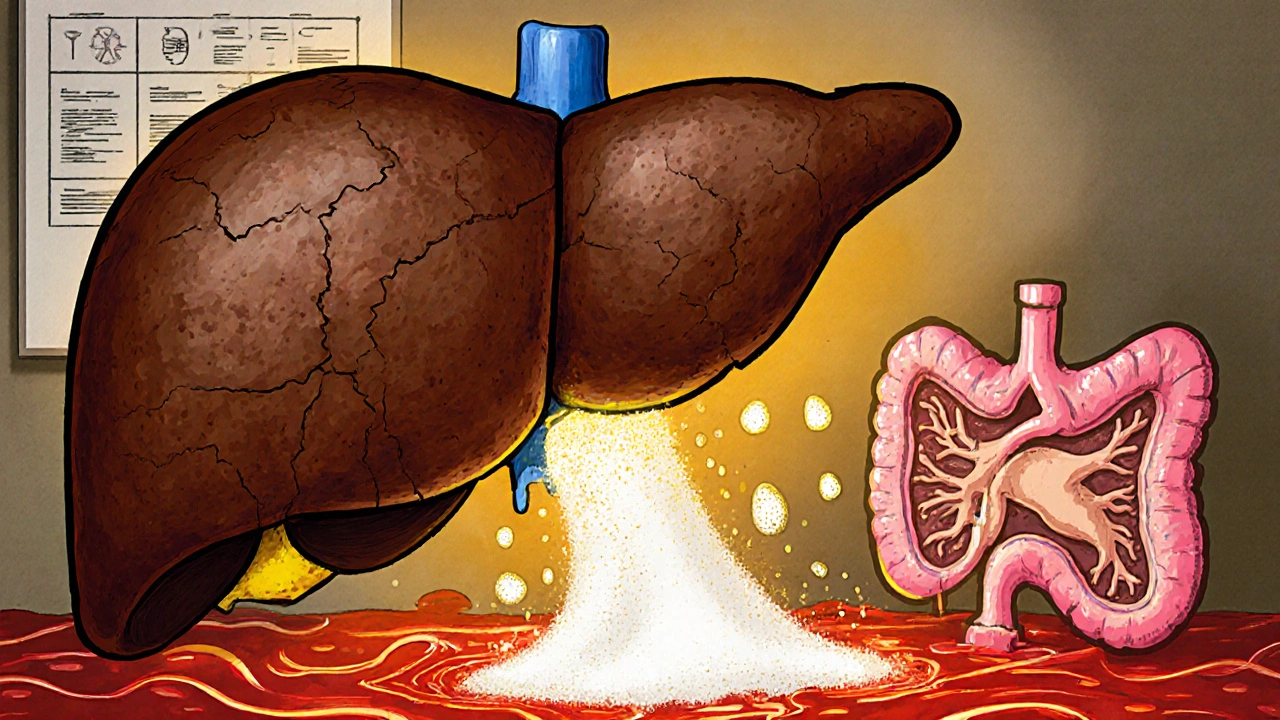

How Diabetes Accelerates Liver Damage

It’s a two‑way street. High blood sugar harms the liver in several ways:

- Excess glucose fuels fat deposition in liver cells, worsening NAFLD and speeding progression to Cirrhosis.

- Advanced glycation end‑products (AGEs) trigger oxidative stress, which accelerates hepatocyte death.

- Microvascular damage impairs the liver’s blood supply, raising risk of Portal hypertension and related complications.

In short, the more uncontrolled the glucose, the faster the liver deteriorates.

Spotting the Overlap: Signs, Labs, and Imaging

Early detection saves lives. Look for these red flags when a patient has either condition:

| Indicator | Typical Value in Healthy Adults | Abnormal Value Suggesting Overlap |

|---|---|---|

| HbA1c | 4.0‑5.6 % | >6.5 % (diagnostic for diabetes) ≥8 % often seen in advanced liver disease |

| ALT/AST Ratio | ~1 | >2 indicates hepatocellular injury common in diabetics with fatty liver |

| Serum Albumin | 3.5‑5.0 g/dL | <4 g/dL signals synthetic failure, often concurrent with poor glycemic control |

| Platelet Count | 150‑400 ×10⁹/L | <150 ×10⁹/L suggests portal hypertension and splenic sequestration |

Imaging (ultrasound, FibroScan) can reveal steatosis, fibrosis stage, or cirrhotic nodules. When labs and imaging line up, a comprehensive metabolic assessment is warranted.

Managing Both Conditions Together

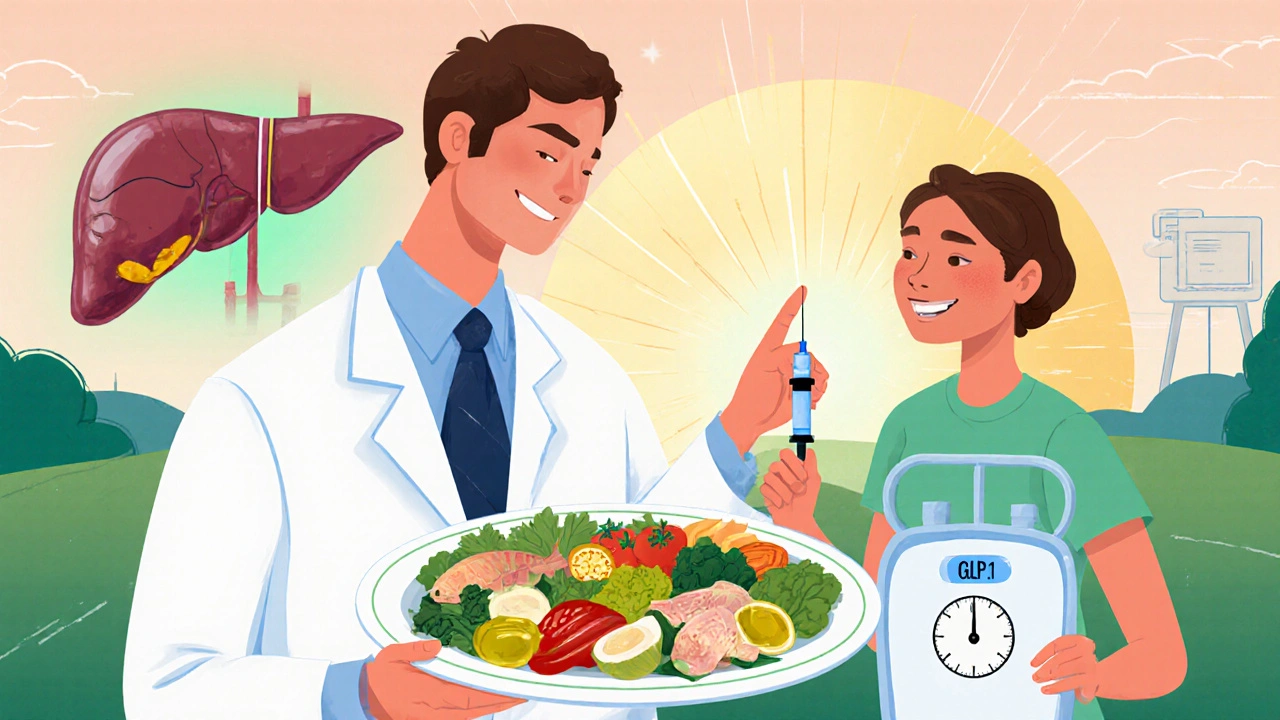

Therapy must hit two birds with one stone. Here are proven strategies:

- Weight loss: A 7‑10 % reduction in body weight improves insulin sensitivity and can downgrade fibrosis by one stage.

- Metformin: First‑line for type 2 diabetes; it also modestly reduces hepatic gluconeogenesis and may lower liver fat. Use with caution if bilirubin > 2 mg/dL.

- GLP‑1 receptor agonists: Agents like semaglutide drop HbA1c and shrink liver fat. Recent 2024 trials show a 30 % remission rate of NASH in diabetics.

- Statins: Control lipid profiles and lower cardiovascular risk-essential because liver disease patients often have high CVD mortality.

- Avoid hepatotoxic meds: Acetaminophen > 4 g/day, high‑dose vitamin A, and certain antibiotics can push a fragile liver over the edge.

- Monitor for complications: Regular screening for hepatic encephalopathy (mental status changes), variceal bleeding (endoscopy), and renal dysfunction (creatinine, electrolytes).

Collaboration between hepatologists, endocrinologists, and dietitians produces the best outcomes.

Common Pitfalls and How to Dodge Them

Even seasoned clinicians trip up. Watch out for these mistakes:

- Assuming normal liver enzymes mean no liver disease: Up to 40 % of diabetics with advanced fibrosis have normal ALT/AST.

- Ignoring the impact of alcohol: Even modest drinking (1‑2 drinks/day) dramatically speeds NAFLD‑to‑cirrhosis conversion in diabetics.

- Over‑reliance on HbA1c: Anemia or chronic liver disease can skew HbA1c low; consider fructosamine or continuous glucose monitoring.

- Not adjusting drug doses: Many oral hypoglycemics require dose reductions when Child‑Pugh class B or C.

By staying alert to these red flags, you can prevent a cascade of complications.

When to Seek Specialist Care

Early referral can halt progression. Schedule a hepatology consult if any of the following appear:

- Persistent ALT/AST > 2 × upper limit of normal.

- HbA1c > 9 % despite optimal oral therapy.

- Signs of portal hypertension: ascites, variceal bleeding, or splenomegaly.

- Unexplained encephalopathy, jaundice, or coagulopathy (INR > 1.5).

Specialists can offer liver‑protective pharmacotherapy, assess transplant eligibility, and coordinate diabetes management.

Key Takeaways

- Liver failure drives insulin resistance, uncontrolled gluconeogenesis, and hormonal chaos, all of which spark diabetes.

- High glucose accelerates fat buildup, oxidative stress, and vascular damage, fast‑tracking liver disease.

- Watch labs like HbA1c, ALT/AST ratio, albumin, and platelet count; imaging adds a powerful visual cue.

- Weight loss, metformin, GLP‑1 agonists, and statins form a therapeutic backbone that tackles both organs.

- Never rely solely on liver enzymes or HbA1c-both can mislead in the setting of chronic disease.

Can type 1 diabetes cause liver failure?

Directly, type 1 diabetes rarely harms the liver. However, long‑term poor control can lead to fatty liver, which may progress to fibrosis and eventually failure if untreated.

Is it safe to use metformin if I have cirrhosis?

Metformin is generally safe in compensated cirrhosis (Child‑Pugh A). In decompensated cases (B or C), dose reduction or alternative agents are recommended to avoid lactic acidosis.

How often should a diabetic with liver disease get liver imaging?

Guidelines suggest an abdominal ultrasound or FibroScan every 1‑2 years, or sooner if liver enzymes rise or symptoms appear.

Do GLP‑1 agonists improve liver outcomes?

Yes. Recent trials (2024) show a 30 % remission rate of NASH and significant reductions in liver fat on MRI in diabetic patients using semaglutide.

What lifestyle changes matter most?

A Mediterranean‑style diet, regular aerobic exercise (150 min/week), and limiting alcohol to < 1 drink/day are the three biggest factors that improve both insulin sensitivity and liver health.

Comments(10)