Hypoglycemia Treatment Calculator

Hypoglycemia Treatment Calculator

Calculate how much fast-acting carbohydrates you need to safely treat low blood sugar following the 15-15 rule.

Low blood sugar isn't just a nuisance-it can be dangerous. If you're taking insulin, sulfonylureas, or meglitinides for diabetes, you're at real risk of hypoglycemia. Blood glucose below 70 mg/dL triggers symptoms like shaking, sweating, and confusion. Below 54 mg/dL, you risk seizures or passing out. This isn't theoretical. One in four type 1 diabetes patients develops hypoglycemia unawareness after 15 years. And it’s not just about feeling bad-it’s about survival.

Which Diabetes Medications Cause the Most Low Blood Sugar?

Not all diabetes drugs are created equal when it comes to hypoglycemia risk. Insulin and sulfonylureas are the biggest culprits. Glimepiride, glipizide, and glyburide cause low blood sugar in 15-30% of users every year. Meglitinides like repaglinide aren’t far behind at 10-20%. Insulin users? Rates jump to 20-40%, especially with multiple daily injections or older insulin types.

Compare that to metformin-less than 5% risk. GLP-1 agonists like semaglutide? Under 2%. SGLT2 inhibitors like empagliflozin? Around 3%. That’s why doctors often start with metformin before adding anything stronger. If you’re on a sulfonylurea and keep getting low, ask if switching to a newer agent makes sense.

Even within insulin types, there’s a difference. Fast-acting analogs like insulin lispro or aspart reduce hypoglycemia by 19% compared to regular human insulin. Why? They act quicker and clear faster, matching meals better. Older insulins linger longer, increasing the chance of a crash hours after eating.

Who’s Most at Risk?

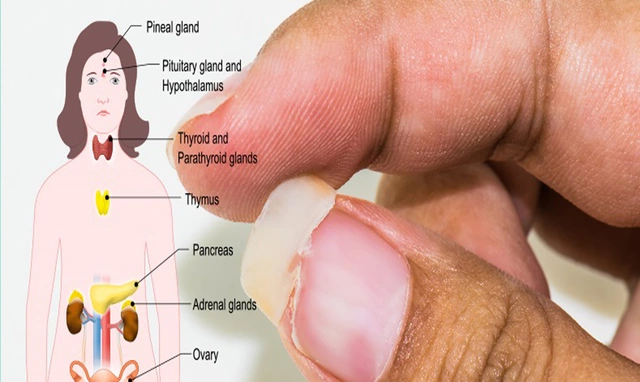

Age matters. People over 65 have a 40% higher risk of severe hypoglycemia. Why? Kidneys slow down, so medications stick around longer. Liver function drops, making it harder to release stored sugar. And many older adults take beta-blockers for blood pressure-which hide the warning signs like sweating and shaking. You might not feel it until you’re confused or passing out.

Long-term diabetes? After 15 years, your body’s natural defenses against low blood sugar start to fade. That’s hypoglycemia unawareness. You stop getting the warning signals. It affects 25% of type 1 patients and 10% of type 2 patients after a decade or more. This isn’t just inconvenient-it’s life-threatening.

Other red flags: kidney disease (eGFR under 60 triples your risk), skipping meals, drinking alcohol without food, or exercising without adjusting carbs or meds. Alcohol blocks your liver from releasing glucose. Exercise burns through sugar fast. Both are common triggers.

How to Recognize and Treat Low Blood Sugar

There are two types of symptoms. Autonomic ones-sweating, trembling, hunger, rapid heartbeat-happen around 65-70 mg/dL. These are your body’s alarm system. Neuroglycopenic symptoms-confusion, drowsiness, slurred speech, seizures-kick in below 55 mg/dL. That’s when your brain is starving. If you’re experiencing these, you need help immediately.

The 15-15 rule works for mild to moderate lows: eat 15 grams of fast-acting carbs, wait 15 minutes, check again. Glucose tablets are ideal-14 grams per tablet. Juice? 4 ounces. Regular soda? Same. Don’t use diet drinks, sugar-free candy, or complex carbs like bread or peanut butter. They’re too slow.

Once your sugar’s back above 70, eat a snack with protein and carbs if your next meal is more than an hour away. A piece of toast with peanut butter, or cheese with crackers. This prevents a rebound crash.

If you’re unconscious or can’t swallow, you need glucagon. Newer nasal glucagon (Baqsimi) takes seconds to use-no mixing, no needles. The old injectable kits require prep time you might not have. Keep one in your bag, your car, your desk. Make sure family, coworkers, or roommates know where it is and how to use it.

Technology That Actually Helps

Continuous glucose monitors (CGMs) are game-changers. They track your sugar every 5 minutes and alert you when you’re dropping. The DIAMOND trial showed CGMs cut severe lows by 48%. You don’t have to poke your finger every time. You can see trends-like if your sugar drops after dinner or during the night.

But cost is a barrier. Dexcom G7 runs about $399 every three months. Freestyle Libre 3 is $89 a month. Medicare now covers CGMs for insulin users, but out-of-pocket costs still hit low-income patients hard. Only 19% of those earning under $30,000 use them, compared to 71% of those earning over $100,000.

Smart insulin pens are another tool. They track doses, timing, and even remind you if you’ve missed a shot. Some sync with apps to show patterns. They cost around $150 upfront, with sensors at $50/month. Not cheap, but they reduce guesswork.

Insulin pumps with automated features-like Tandem’s Control-IQ-can pause insulin delivery when your sugar drops. Studies show they cut nighttime lows by over 3 hours. But they cost $6,500 a year. Not everyone can access them.

What You Can Do Right Now

Start tracking. Log every low: what you ate, when you took meds, how much you moved, your blood sugar before and after. The Joslin Diabetes Center found patients who kept detailed logs reduced lows by 52% in six months. Just 10-15 minutes a day. Use a notebook or an app like Glooko. The key? Consistency. Only 28% of people keep logging beyond six weeks. Don’t be one of them.

Build a ‘hypo bag.’ Keep glucose tablets, glucagon, a snack, and a medical ID bracelet in your purse, car, and work bag. 54% of patients who use this strategy say it saved them. Don’t wait until you’re low to realize you forgot your tablets.

Set phone alarms for meals and meds. 67% of users who do this report fewer lows. Missing a meal or taking insulin too early is a common mistake. Alarms help you stay on schedule.

Get trained. The ADA’s ‘Hypoglycemia Uncovered’ program cuts events by 45% with just one hour of focused education. Learn how to count carbs in grams, not ‘servings.’ Most people guess wrong. A small apple is 15 grams. A banana? 30. A granola bar? Often 25. Know your numbers.

When to Talk to Your Doctor

If you’ve had two or more lows in a month, it’s time to revisit your treatment plan. Don’t wait until you pass out. Ask: Is my HbA1c target realistic? Are my meds too strong? Could I switch to a lower-risk drug?

The ADA now recommends individualized goals. For most adults, 70-130 mg/dL before meals is fine. But for older adults with other health issues? 80-130 mg/dL. For someone with hypoglycemia unawareness? Maybe 90-150 mg/dL. Lower isn’t always better.

Ask about the 8-point hypoglycemia risk score. It’s used by endocrinologists to predict who’s most likely to have a severe event. It looks at age, kidney function, medication type, history of lows, and more. A simple tool that saves lives.

And if you’re on beta-blockers, tell your doctor. They can’t always tell you’re having a low. You might need a different blood pressure med-or more frequent checks.

What’s Coming Next

Technology is moving fast. Dasiglucagon, approved in 2023, is a liquid glucagon that doesn’t need mixing. Ready in 10 seconds. No more fumbling with vials during an emergency.

Predictive low-glucose suspend systems are getting smarter. They use algorithms to anticipate drops before they happen. Early data shows they cut hypoglycemia duration by 42% without raising HbA1c.

By 2030, most insulin users will likely be on closed-loop systems-devices that automatically adjust insulin based on real-time glucose. They could cut severe lows by 65%. But access won’t be equal. Cost, insurance, and education gaps will still leave many behind.

Right now, the best tool you have is knowledge. Know your meds. Know your triggers. Know your numbers. And never, ever ignore a low. Even if it feels minor. Because the next one might not be so easy to fix.

Can metformin cause low blood sugar?

No, metformin alone rarely causes hypoglycemia. Its risk is under 5%. It works by reducing liver sugar production and improving insulin sensitivity-not by forcing your body to release more insulin. But if you take metformin with insulin or sulfonylureas, your risk goes up. Always check your combo meds.

Is it safe to drive with diabetes and hypoglycemia risk?

Yes-but only if you take precautions. Check your blood sugar before driving. Never drive if it’s below 70 mg/dL. Keep glucose tablets in the car. If you feel shaky or confused while driving, pull over immediately. People with hypoglycemia unawareness should avoid driving alone or long distances without a passenger who knows how to help.

Why do I get low blood sugar at night?

Nighttime lows happen because your body’s insulin needs drop while you sleep, but your meds don’t. Long-acting insulin or sulfonylureas can keep working past bedtime. Eating too little at dinner, drinking alcohol, or exercising in the evening increases risk. A small bedtime snack with protein and complex carbs can help. CGMs are best for catching these silent drops.

Can I stop my diabetes meds if I keep getting low?

Never stop your meds without talking to your doctor. Stopping insulin or sulfonylureas suddenly can cause dangerous high blood sugar. Instead, ask your provider to adjust your dose, switch to a lower-risk drug, or add a CGM. There are safer ways to manage your diabetes without risking lows.

Do I need glucagon if I only take metformin?

Probably not. Glucagon is only needed if you’re on insulin, sulfonylureas, or meglitinides. If you’re only on metformin, GLP-1 agonists, or SGLT2 inhibitors, your risk of severe hypoglycemia is very low. But if you’re on any combination that includes insulin or sulfonylureas-even occasionally-keep glucagon on hand.

Comments(12)