When you fill a prescription for a generic drug-say, lisinopril for high blood pressure or metformin for diabetes-you might assume the price you see at the pharmacy is what your insurance paid. It’s not. And that’s where things get messy.

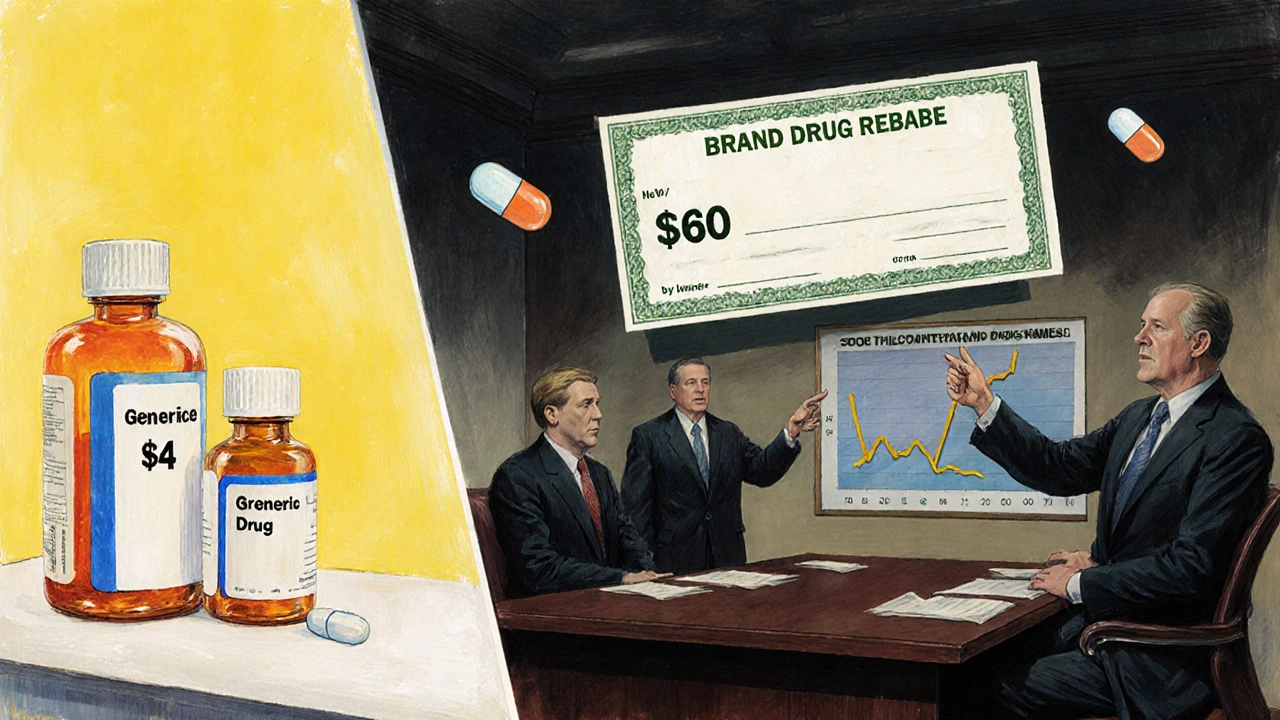

Generics don’t get rebates like brand-name drugs

Most people think rebates are how drug prices get lowered. That’s true for brand-name drugs. Companies like Pfizer or Merck offer big discounts-sometimes 30% to 70% off the list price-to pharmacy benefit managers (PBMs) like CVS Caremark or Express Scripts. In return, those PBMs put the brand drug on the preferred tier, meaning it’s cheaper for you to take it.

But generics? They don’t play by those rules. Because dozens of companies make the same generic version of a drug-no patent, no exclusivity-the price is already low. There’s no need for a rebate. If one maker drops their price to $2 per pill, another will drop to $1.80. Competition drives the price down, not rebates.

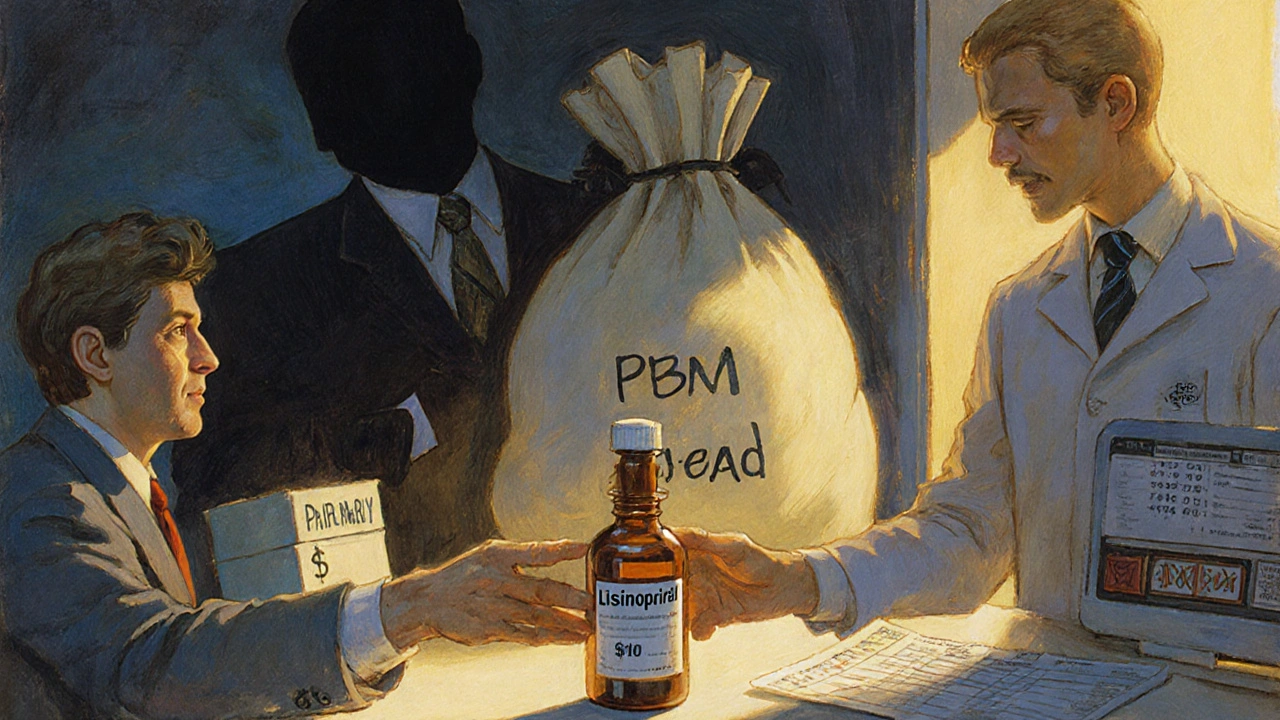

So what does your insurance actually pay? It’s not what you think.

What insurers pay for generics isn’t the same as what pharmacies get paid

Here’s the hidden layer: PBMs don’t rely on rebates for generics. They make money through something called spread pricing.

Let’s say your insurance plan agrees to reimburse the pharmacy $10 for a 30-day supply of generic atorvastatin. That’s the amount your insurer thinks it’s paying. But the PBM only pays the pharmacy $5. The other $5? The PBM keeps it. That’s the spread. No rebate. No transparency. Just a hidden profit built into the system.

This isn’t rare. The U.S. Department of Health and Human Services found that in 2022, the average spread between what PBMs charged plans and what they paid pharmacies for generics was $4.73 per prescription. Multiply that by millions of prescriptions, and you’re talking billions in hidden fees.

And here’s the kicker: your insurance plan doesn’t always know this is happening. Many employers and health plans sign contracts with PBMs that don’t require them to disclose how much they’re really paying pharmacies. So even if your plan says it’s saving money on generics, it might just be paying more than it thinks.

Why PBMs prefer brand-name drugs-even when generics are cheaper

It sounds backwards, but it’s true: PBMs sometimes push expensive brand-name drugs over cheaper generics-not because they’re better, but because they make more money.

Brand-name drugs come with big rebates. If a PBM gets a 60% rebate on a $100 brand drug, that’s $60 back in their pocket. A generic that costs $5? Even if the manufacturer offers a 5% rebate, that’s just 25 cents. So PBMs have a financial incentive to keep brand-name drugs on the formulary-even if a generic exists and costs less.

Studies from the Commonwealth Fund and Rightway Healthcare show this isn’t theoretical. In one case, a PBM excluded a $0.15-per-dose generic version of a drug in favor of a $5-per-dose brand-name version with a 60% rebate. The net cost to the insurer? Higher. The patient? Still paying the same copay. The PBM? Pocketing the difference.

This is why you might get denied coverage for a generic. Not because it’s not effective. Not because your doctor didn’t prescribe it. But because the PBM’s rebate deal favors the brand.

How much do generics really save? (Spoiler: a lot-except when they don’t)

Generics make up about 90% of all prescriptions filled in the U.S., but they only account for 23% of total drug spending. That’s because they’re cheap. A generic version of Lipitor costs less than $10 a month. The brand? Over $200.

But when spread pricing hides the real cost, those savings vanish. A 2024 report from the National Business Group on Health found that 68% of large employers couldn’t figure out how much they were really paying for generics. Some thought they were saving $3 per script. Turns out, they were paying $7-because the PBM kept $4 in spread.

And it’s not just employers. Medicare Part D, which covers millions of seniors, doesn’t even negotiate rebates on generics. Why? Because the system assumes the market already keeps prices low. But if PBMs are siphoning off money through spread pricing, that assumption is broken.

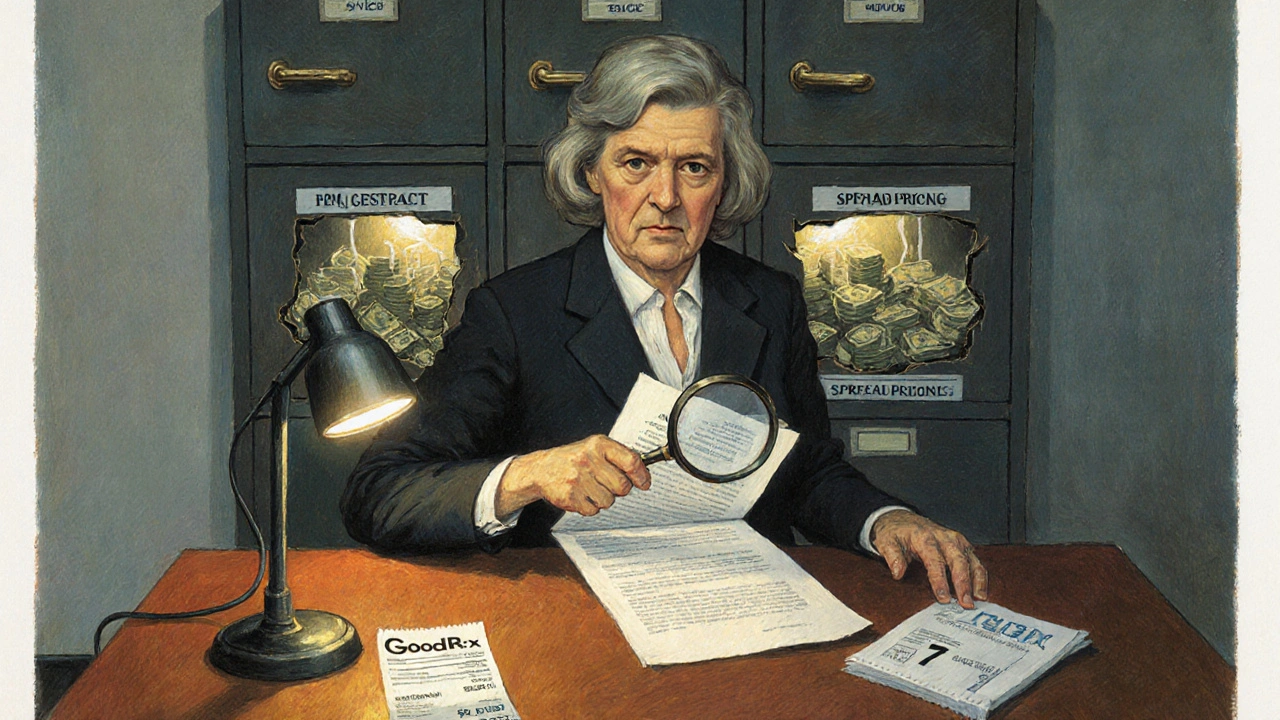

What’s being done to fix this?

There’s growing pressure to change this. The Biden administration’s 2024 Executive Order directed the Department of Health and Human Services to investigate practices that limit generic drug use. In March 2025, CMS announced new rules requiring PBMs to disclose their pricing practices to employers and insurers.

More importantly, a shift is happening toward pass-through pricing. Instead of letting PBMs keep the spread, this model makes them charge a flat administrative fee-say, $2 per prescription-and pay pharmacies the actual cost of the drug. No hidden profits. No guesswork.

In 2020, only 18% of large employers used pass-through models. By 2024, that number jumped to 42%. And it’s not just big companies. More small businesses and union plans are demanding transparency.

Legislation is coming too. The Employee Benefit Research Institute predicts that by 2026, federal rules will require PBMs to fully disclose the acquisition cost of every generic drug. That means no more hiding the spread.

What you can do right now

If you’re on an employer-sponsored plan, ask your HR department: Do we use pass-through pricing for generics? If they don’t know, ask them to check your PBM contract. If you’re on Medicare Part D, check your plan’s formulary. If a generic is being denied, ask why. Request a formulary exception.

Use tools like GoodRx or SingleCare to compare cash prices. Sometimes paying cash for a generic is cheaper than using insurance-especially if your plan has a high deductible or the PBM is hiding the spread.

And if you’re an employer or plan sponsor? Demand transparency. Ask for your PBM’s actual acquisition cost data for top generic drugs. If they refuse, switch. There are now dozens of PBM alternatives that operate on a fee-for-service model, not a profit-from-spread model.

Bottom line: You’re paying more than you think

Generics are still the best way to save money on prescriptions. But the system that’s supposed to help you save is often working against you. Insurance doesn’t pay what you think it does. PBMs are making money behind the scenes. And you’re the one footing the bill-through higher premiums, higher deductibles, or just out-of-pocket costs.

The good news? The tide is turning. More people are asking questions. More employers are demanding honesty. And soon, the hidden spreads may finally be exposed.

Until then, don’t assume your insurance is saving you money on generics. Check. Ask. Compare. Your wallet will thank you.

Do generic drugs ever have rebates?

Rarely, and when they do, the rebates are tiny-usually 2% to 5% of the list price, compared to 30% to 70% for brand-name drugs. Most generics don’t have rebates at all because the market is so competitive that manufacturers already sell them at the lowest possible price. What you see is usually close to what they cost to make.

Why does my insurance say it covered a generic but I still paid a lot?

Your insurance might be covering the drug, but the PBM could be charging your plan more than it pays the pharmacy. For example, your plan might pay $12 for a generic, but the pharmacy only gets $6. The $6 difference is kept by the PBM as spread pricing. You’re paying your copay on the inflated price, while your insurer pays more than it should.

Can I find out what my PBM really paid for my generic drug?

Not easily-yet. Most PBM contracts are secret. But if you’re an employer or part of a large group plan, you can request your PBM’s acquisition cost data. Starting in 2026, federal rules will require full disclosure. In the meantime, use tools like GoodRx to compare cash prices. If the cash price is lower than your copay, pay cash.

Are generics always cheaper than brand-name drugs?

Almost always-but not always when insurance is involved. Sometimes, due to rebate structures, a brand-name drug with a 60% rebate ends up costing your plan less than a generic with no rebate. That’s why your plan might deny coverage for a cheaper generic. It’s not about cost-it’s about rebate profits.

What’s the difference between WAC, AWP, and the actual price?

Wholesale Acquisition Cost (WAC) is what the manufacturer charges the distributor. Average Wholesale Price (AWP) is an outdated, inflated benchmark used by some insurers to calculate payments-it’s often 20% to 50% higher than the real price. The actual price is what the pharmacy pays the distributor. PBMs use AWP to make rebates look bigger, but for generics, the real price is what matters-and it’s usually close to WAC.

Comments(15)