NSAID Kidney Risk Calculator

This calculator estimates your risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) when using NSAIDs based on medical factors and medication combinations mentioned in the article.

Important: This is not a medical diagnosis. Always consult your healthcare provider before making medication decisions.

Your Risk Assessment

Every year, tens of thousands of people end up in the hospital not because of a heart attack or stroke, but because they took something as simple as an ibuprofen pill for a headache or sore knee. It’s not rare. It’s not unusual. And it’s almost always preventable. NSAIDs - nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs like ibuprofen, naproxen, and aspirin - are among the most commonly used medications in the world. You can buy them over the counter in almost every country. But if you have kidney disease, or even just a single risk factor like high blood pressure or dehydration, these pills can quietly shut down your kidneys in days - sometimes hours.

How NSAIDs Actually Damage Your Kidneys

NSAIDs don’t attack your kidneys directly. They don’t poison them. Instead, they take away something your kidneys rely on to survive when things get tough: prostaglandins. These tiny molecules help keep blood flowing into your kidneys, especially when you’re dehydrated, sick, or older. When you take an NSAID, you block the production of prostaglandins. That sounds harmless - until you realize your kidneys need those signals just to stay alive under stress.

In healthy people, this might not matter. But if you’re over 60, have diabetes, high blood pressure, or already have reduced kidney function (eGFR below 60), your kidneys are already running on low. Without prostaglandins to help dilate blood vessels, your kidneys get less blood. Glomerular filtration rate (GFR) can drop 20-40% within 24 hours. That’s not a slow decline. That’s a sudden fall. And it’s called acute kidney injury (AKI).

Studies show that 1-5% of all AKI cases in hospitals are caused by NSAIDs. That’s more than some infections. And it’s not just hospital patients. A 2023 review found that chronic NSAID users have a 24% higher risk of developing chronic kidney disease (CKD) and a 50% higher risk of their existing CKD getting worse. For people who already have CKD, the risk jumps to 67%.

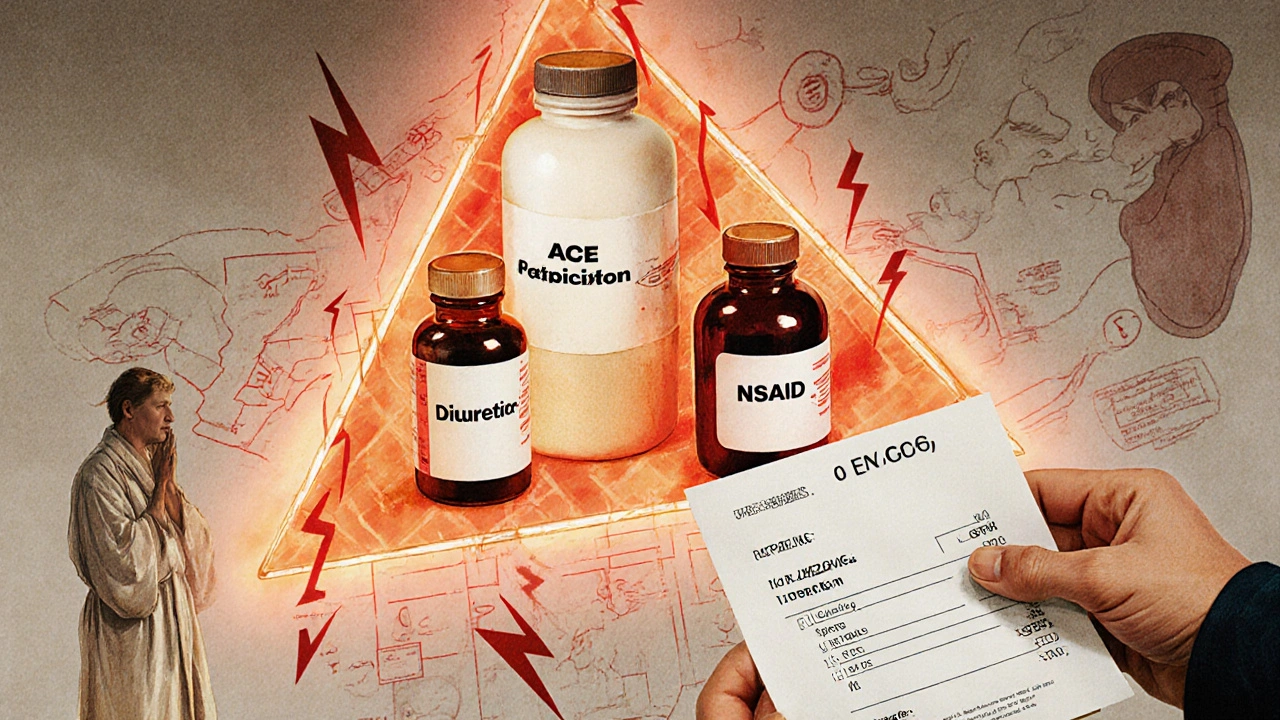

The Triple Whammy: A Deadly Combination

One of the most dangerous things you can do is combine NSAIDs with two other common medications: ACE inhibitors or ARBs (like lisinopril or losartan) and diuretics (like furosemide). This combo is called the “triple whammy.”

Here’s why it’s so risky:

- ACE inhibitors/ARBs lower blood pressure by relaxing blood vessels - including those going to your kidneys.

- Diuretics make you pee more, which lowers blood volume.

- NSAIDs block prostaglandins, which normally help your kidneys compensate for low blood pressure or volume.

Together, they leave your kidneys with no backup plan. A 2013 Medsafe analysis showed this combination increases AKI risk by 31%. But within the first 30 days? Risk jumps to 82%. That’s not a coincidence. That’s a red flag.

Doctors often prescribe these drugs together for heart failure or hypertension. But few patients are warned about the danger. A 2023 survey of nephrologists found that 58% say patients rarely understand this risk - even when they’ve been told to take their pills daily.

Who’s Most at Risk?

Not everyone who takes NSAIDs gets kidney damage. But certain people are sitting on a ticking clock:

- People over 65: Kidney function naturally declines with age. Prostaglandin reserves are lower.

- Those with eGFR below 60: This means your kidneys are already working at less than 60% capacity. NSAIDs can push them into failure.

- People with diabetes or high blood pressure: These conditions already strain the kidneys. NSAIDs add pressure.

- Those taking diuretics, ACE inhibitors, or ARBs: The triple whammy isn’t theoretical - it’s common.

- People who exercise intensely or are dehydrated: Marathon runners, construction workers, or anyone sweating heavily who takes NSAIDs are at higher risk. Studies show NSAIDs can reduce kidney blood flow by 30-50% beyond normal exercise stress.

One case from the University of Rhode Island tells the story: a 72-year-old man with an eGFR of 58 (mildly reduced) started taking 800 mg of ibuprofen three times a day for arthritis. Within 72 hours, his eGFR dropped to 22. He needed hospitalization. He had no prior kidney problems. No symptoms. Just pills.

What Symptoms Should You Watch For?

Here’s the scary part: you might not feel anything until it’s too late.

Acute kidney injury often has no pain, no fever, no obvious signs. But some early signals include:

- Less urine output - you’re peeing less than usual, or not at all for a day.

- Swelling in your ankles, feet, or hands - fluid builds up because your kidneys can’t filter it.

- Unexplained fatigue or confusion - toxins build up in your blood.

- Nausea or vomiting - not from food poisoning, but from rising waste levels.

And here’s something most people don’t know: up to 30% of early AKI cases show no rise in serum creatinine - the standard blood test doctors use to check kidney function. That means your test could look normal while your kidneys are already failing.

What About Acetaminophen? Is It Safer?

If you need pain relief and have kidney disease, acetaminophen (Tylenol) is generally the best alternative. It doesn’t affect prostaglandins the way NSAIDs do. Studies show it carries 40-50% less risk of AKI.

But it’s not perfect. Too much acetaminophen can damage your liver. Stick to the lowest effective dose - no more than 3,000 mg per day if you have liver issues, and never combine it with alcohol.

Opioids are another option for severe pain, but they come with addiction risks (15-25% dependence rate) and constipation. They don’t hurt your kidneys directly, but they’re not ideal for long-term use.

Topical NSAIDs: A Safer Way to Use Them

If you need the anti-inflammatory power of NSAIDs - say, for arthritis in your knee or shoulder - consider a topical gel or patch. These deliver the drug directly to the sore area with very little entering your bloodstream.

A 2024 JAMA Internal Medicine trial with 3,200 patients found topical NSAIDs caused 40-50% fewer cases of AKI compared to pills. They’re not strong enough for full-body pain, but for localized joint pain? They’re a game-changer.

How to Prevent Kidney Injury - A 4-Step Plan

If you’re at risk, here’s what you need to do:

- Get your kidney numbers checked - Ask for an eGFR and urine albumin-to-creatinine ratio before starting any long-term NSAID use. If your eGFR is below 60, NSAIDs should be avoided unless absolutely necessary.

- Avoid the triple whammy - Never take NSAIDs with ACE inhibitors, ARBs, and diuretics together. Talk to your doctor about alternatives.

- Limit duration - Don’t use NSAIDs for more than 7-10 days without checking in with a provider. For chronic pain, use them no more than 3 days a week.

- Stay hydrated - Especially if you’re active or in hot weather. Drink 5-10 mL per kg of body weight 2-4 hours before exercise, and 0.4-0.8 liters per hour during activity. This keeps your urine specific gravity below 1.020 - a sign you’re not dehydrated.

The American Geriatrics Society’s 2023 Beers Criteria says it clearly: NSAIDs should be avoided entirely if your eGFR is below 30. And even between 30 and 60, use them with extreme caution - lowest dose, shortest time.

What’s Changing in 2025?

There’s new hope. In 2024, the American Society of Nephrology launched the NSAID-RF Risk Calculator. It uses 12 factors - age, blood pressure, eGFR, diuretic use - to predict your 30-day AKI risk with 87% accuracy. If you’re on NSAIDs, ask your doctor if you can use it.

Researchers are also testing a new ibuprofen-acetylcysteine combo that protects kidney tissue from oxidative damage. Early trials look promising.

And in 2025, a breakthrough in genetics identified variants in the PTGS2 gene that may predict who’s most likely to suffer kidney damage from NSAIDs. Soon, we may be able to test for personal risk - not just population risk.

For now, the best tool you have is awareness. Your kidneys don’t scream. They whisper. And if you’re ignoring the signs - or worse, never knew there were signs - you’re playing Russian roulette with your health.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I take ibuprofen if I have mild kidney disease?

If your eGFR is between 30 and 60, you should avoid ibuprofen unless absolutely necessary. Even then, use the lowest dose for the shortest time - no more than 3 days a week. Always talk to your doctor first. There’s a 5.8-fold higher risk of acute kidney injury in this group. Acetaminophen is safer.

Do all NSAIDs affect the kidneys the same way?

No. Non-selective NSAIDs like ibuprofen and naproxen carry higher kidney risk than selective COX-2 inhibitors like celecoxib. But the difference shrinks if your kidney function is already low (eGFR below 60). Even celecoxib isn’t safe in advanced kidney disease. Topical NSAIDs are much safer than pills.

Why don’t doctors warn patients about NSAID kidney risks?

Many doctors assume patients know NSAIDs are risky - but they’re not. A 2023 survey found that 72% of patients who suffered NSAID-induced AKI said their doctor never mentioned kidney risks. Over-the-counter status creates a false sense of safety. Patients think, “If it’s sold on a shelf, it must be safe.” That’s not true.

Can NSAIDs cause permanent kidney damage?

Yes. While many cases of NSAID-induced AKI are reversible, some people never fully recover. Chronic use, especially in those with pre-existing kidney disease, can accelerate progression to end-stage kidney failure. The 2023 systematic review showed a 50% increased risk of CKD progression in chronic users.

Is it safe to take NSAIDs after a workout?

It’s not recommended. Exercise reduces kidney blood flow naturally. NSAIDs reduce it further. In hot weather or if you’re dehydrated, this combo can trigger acute kidney injury. Marathon runners who take NSAIDs have a higher risk, even if the overall rate is low. Stick to hydration and rest. If you need pain relief, try acetaminophen or ice.

What to Do Next

If you’re taking NSAIDs regularly - even just a few times a week - check your kidney numbers. Ask your doctor for an eGFR and urine test. If you’re on blood pressure meds or diuretics, review your entire medication list. Don’t assume it’s safe just because it’s available without a prescription.

For chronic pain, explore alternatives: physical therapy, weight management, heat/cold therapy, or topical NSAIDs. If you’re an athlete, hydrate before, during, and after exercise. Don’t reach for the pill bottle as your first response to soreness.

Kidney damage from NSAIDs isn’t inevitable. It’s predictable. And it’s preventable. The only thing standing between you and kidney failure might be one conversation with your doctor - and one decision to put the pill back on the shelf.

Comments(15)