More than 480 million people worldwide live with type 2 diabetes, and each year new drugs promise better control. Among the older options, Actos (Pioglitazone) still shows up in prescribing charts, but clinicians often wonder whether it truly stacks up against newer classes. This guide breaks down how Actos works, compares it side‑by‑side with the most common alternatives, and gives you a practical framework for picking the right pill for a given patient.

What is Actos (Pioglitazone) and How Does It Work?

Actos belongs to the thiazolidinedione (TZD) family. It activates the peroxisome proliferator‑activated receptor‑gamma (PPAR‑γ) in fat, muscle, and liver cells, which improves insulin sensitivity and reduces hepatic glucose output. The result is lower fasting glucose and modest reductions in HbA1c (typically 0.5‑1.4 %). It’s taken once daily, usually 15 mg or 30 mg, and can be combined with metformin, sulfonylureas, or insulin.

Pioglitazone received FDA approval in 1999 and has a solid safety record when used as directed, but it carries warnings for heart failure, bone fractures, and, historically, a debated bladder‑cancer risk. Monitoring liver enzymes before starting and periodically thereafter is standard practice.

Major Alternative Classes for Type 2 Diabetes

Since the early 2000s, several new drug classes have entered the market. Below is a quick snapshot of each, with the most representative agents highlighted.

- Metformin - a biguanide that reduces hepatic glucose production and improves peripheral insulin sensitivity. Often the first‑line choice.

- SGLT2 inhibitors (e.g., Empagliflozin) - block glucose reabsorption in the kidney, leading to urinary glucose loss.

- DPP‑4 inhibitors (e.g., Sitagliptin) - increase endogenous GLP‑1 levels, modestly lowering glucose.

- GLP‑1 receptor agonists (e.g., Liraglutide) - mimic the incretin hormone GLP‑1, enhancing insulin secretion and promoting weight loss.

- Sulfonylureas (e.g., Glipizide) - stimulate pancreatic beta‑cells to release more insulin.

- Rosiglitazone - another TZD, largely withdrawn in many markets due to cardiovascular concerns, but still useful for historical context.

Head‑to‑Head: Efficacy and Glycemic Control

When you compare HbA1c reduction, the numbers look roughly like this:

- Metformin: -1.0 % to -1.5 % (baseline monotherapy)

- Actos (Pioglitazone): -0.5 % to -1.4 %

- SGLT2 inhibitors (Empagliflozin): -0.6 % to -1.0 %

- DPP‑4 inhibitors (Sitagliptin): -0.5 % to -0.8 %

- GLP‑1 agonists (Liraglutide): -0.8 % to -1.3 %

- Sulfonylureas (Glipizide): -0.8 % to -1.2 %

In pure numbers, Actos sits squarely in the middle. It’s not the strongest reducer, but it offers a reliable drop, especially when combined with metformin.

Weight Impact and Cardiovascular Profile

Weight change is a major patient concern. Here’s the typical direction for each class:

- Metformin: modest weight loss or neutral.

- Actos: modest weight gain (1‑3 kg) due to fluid retention.

- SGLT2 inhibitors: weight loss (2‑3 kg) from calorie loss in urine.

- DPP‑4 inhibitors: neutral.

- GLP‑1 agonists: significant weight loss (3‑6 kg) driven by appetite suppression.

- Sulfonylureas: weight gain (1‑2 kg).

Regarding cardiovascular outcomes, the PROactive trial showed that pioglitazone reduced the composite endpoint of all‑cause mortality, non‑fatal MI, and stroke by about 16 % in patients with prior macrovascular disease. Meanwhile, SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP‑1 agonists have robust FDA‑approved cardiovascular‑risk‑reduction labels. Metformin’s benefit is more modest but still present.

Side‑Effect Landscape

Understanding tolerability is key. Below is a quick risk snapshot.

| Drug | Common Adverse Events | Serious Risks |

|---|---|---|

| Actos | Weight gain, edema, mild GI upset | Heart failure exacerbation, bone fracture, possible bladder cancer (controversial) |

| Metformin | GI upset, metallic taste | Lactic acidosis (rare) |

| Empagliflozin | Genital mycotic infections, polyuria | Euglycemic DKA, volume depletion, rare amputations |

| Sitagliptin | Nasopharyngitis, headache | Pancreatitis (very rare), severe joint pain |

| Liraglutide | Nausea, vomiting, diarrhea | Pancreatitis, gallbladder disease, possible thyroid C‑cell tumors (animal data) |

| Glipizide | Hypoglycemia, GI upset | Severe hypoglycemia especially in renal impairment |

Notice how Actos shares the fluid‑retention issue with thiazolidinediones, while SGLT2 inhibitors tend to cause dehydration instead. Choosing a drug often means balancing these opposite risks based on a patient’s comorbidities.

Cost Considerations (2025 US Prices)

Drug price can decide whether a prescription gets filled. Approximate monthly costs for a typical dose (based on major US pharmacy data, 2025):

- Actos (generic pioglitazone): $15‑$25

- Metformin (generic): $4‑$10

- Empagliflozin (generic slated 2026): $250‑$300 (brand: Jardiance $350)

- Sitagliptin (generic): $100‑$130

- Liraglutide (brand: Victoza): $800‑$900

- Glipizide (generic): $8‑$12

Actos remains one of the most affordable options that still offers a distinct mechanism, which can be a decisive factor in low‑resource settings.

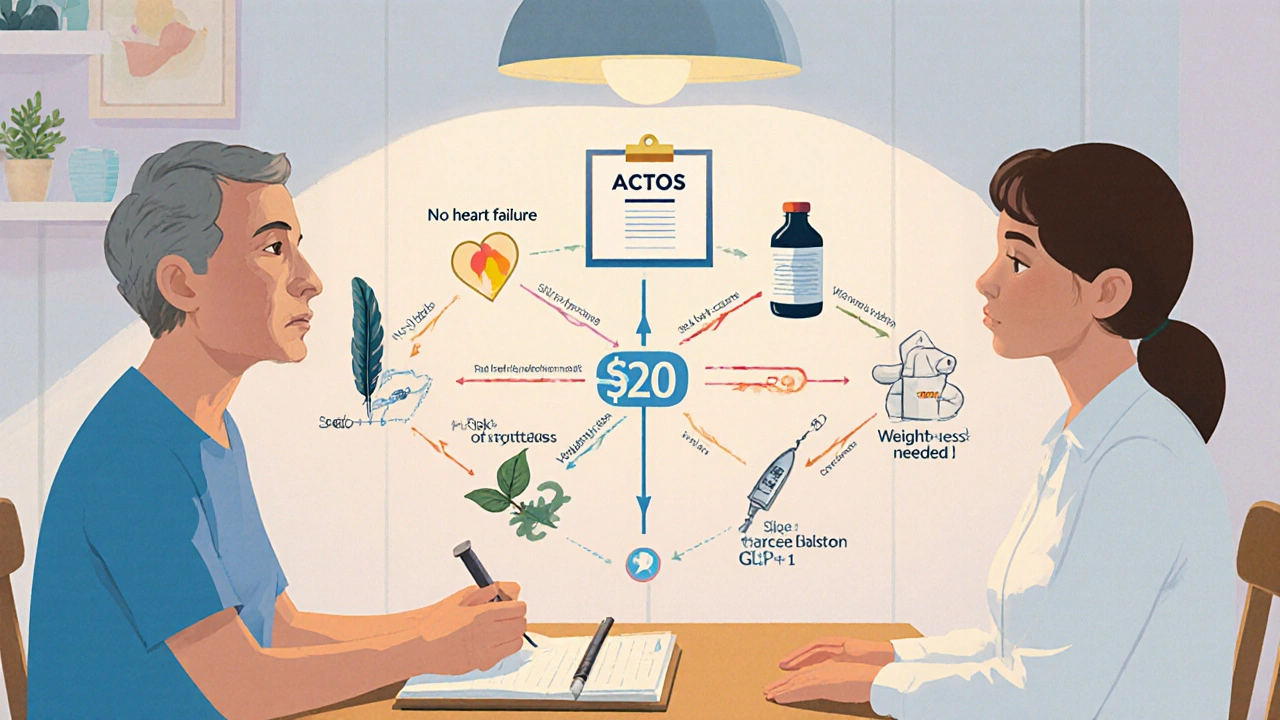

When to Choose Actos Over Alternatives

Here’s a quick decision tree:

- If the patient is already on metformin but needs additional HbA1c reduction and has no heart‑failure history → consider adding Actos.

- If the patient has a history of bone fractures or osteoporosis → avoid Actos; favor SGLT2 inhibitors or GLP‑1 agonists.

- If cost is a major barrier and the patient cannot afford newer agents → Actos offers a cheap, potent insulin‑sensitizer.

- If the patient is already fluid‑overloaded or has NYHA II‑IV heart failure → skip Actos; opt for SGLT2 inhibitors (which actually improve heart‑failure outcomes).

- For patients who need weight loss as a therapeutic goal → GLP‑1 agonists or SGLT2 inhibitors are superior.

In practice, many clinicians use a “metformin + pioglitazone” combo for patients with moderate insulin resistance who cannot tolerate SGLT2 inhibitors due to recurrent urinary infections.

Practical Tips for Initiating Pioglitazone

- Check baseline liver enzymes (ALT/AST) and repeat in 3 months.

- Screen for heart‑failure signs (edema, dyspnea) before starting.

- Start at 15 mg daily; if HbA1c remains >0.5 % above target after 12 weeks, uptitrate to 30 mg.

- Educate patients about possible weight gain and advise monitoring daily weight.

- Consider calcium‑vitamin D supplementation in patients with osteoporosis risk.

These steps keep the safety profile favorable and reduce the likelihood of discontinuation.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can I take Actos with insulin?

Yes. Pioglitazone can be added to basal or prandial insulin to improve sensitivity, but watch for hypoglycemia and adjust insulin dose accordingly.

Is the bladder‑cancer warning still relevant?

Epidemiologic data are mixed. The FDA requires a label warning, but the absolute risk increase is small (<1 case per 10,000 patient‑years). Discuss the issue with patients who have a history of urothelial cancer.

How does Actos compare to metformin in early‑stage diabetes?

Metformin remains the first‑line choice because it’s weight‑neutral, inexpensive, and has a strong safety record. Actos is usually added later when metformin alone does not achieve target HbA1c.

What monitoring is needed after starting pioglitazone?

Check liver enzymes at baseline and at 3 months. Assess weight and edema at each visit. In patients with osteoporosis, consider bone‑density testing annually.

Are there any drug‑drug interactions I should watch for?

Pioglitazone is metabolized by CYP2C8; strong inhibitors like gemfibrozil can raise levels. Combine with other CYP2C8 substrates (e.g., repaglinide) cautiously.

Bottom Line

Actos offers a cheap, insulin‑sensitizing punch that still has a role in modern diabetes care, especially when cost constraints or specific patient characteristics (e.g., heart‑failure‑free, no fracture risk) line up. Newer agents win on weight loss and cardiovascular outcomes, but they also carry higher price tags and unique side‑effects. By weighing efficacy, safety, cost, and individual comorbidities, clinicians can decide whether pioglitazone belongs in a patient’s regimen or whether an alternative class is a better fit.

Comments(12)