Amoeba Prevention Impact Calculator

Estimated Reduction in Cases

0

cases prevented annually

School-Based Curriculum

Trains students and families on hygiene practices

Community Campaigns

Reinforces messages across all age groups

Combined Approach

Maximum impact through synergy

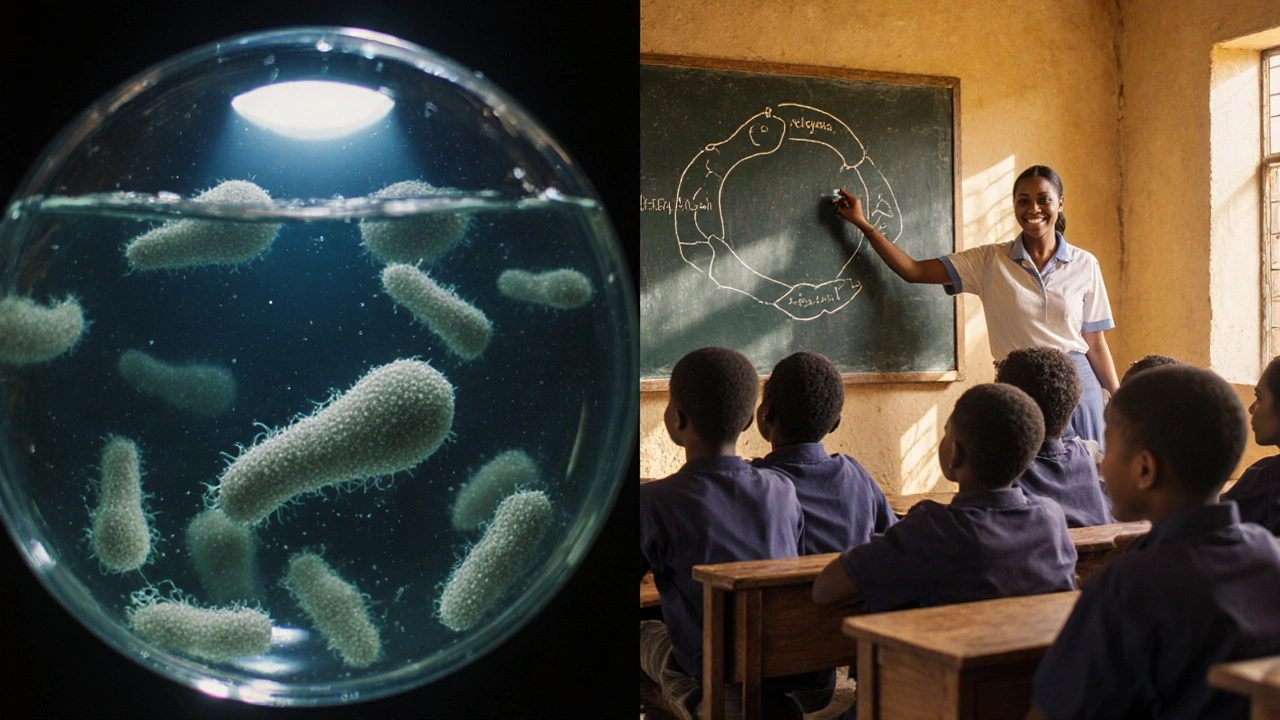

When you hear the word "amoeba," you probably picture a single‑cell organism floating in a pond. Amoeba infection is a real health threat, especially in regions where water and food safety are shaky. The good news? A lot of those cases can be avoided simply by teaching people what to look out for. This article shows how education becomes the first line of defense against a disease most of us only hear about in textbooks.

What exactly is an amoeba infection?

Entamoeba histolytica is the parasite responsible for the majority of severe cases. When someone swallows cysts-usually from contaminated water, raw vegetables, or unwashed hands-the parasite can invade the intestine, causing symptoms ranging from mild diarrhea to life‑threatening dysentery. The World Health Organization estimates that up to 50million people worldwide develop amoebiasis each year, with roughly 100000 deaths, most of them in low‑resource settings.

Why education matters more than medicine alone

Antiprotozoal drugs like metronidazole work well, but they’re only effective after infection has taken hold. preventing amoeba infections hinges on breaking the transmission chain before cysts reach a person’s mouth. That’s where knowledge, habits, and community norms step in. Studies from Bangladesh (2022) and Peru (2023) showed a 40% drop in new cases after schools introduced a simple curriculum on water safety and hand‑washing. The data tells us that turning facts into everyday practices cuts the disease at its source.

Key educational pillars that stop the spread

- Hand hygiene: Proper hand‑washing with soap for at least 20 seconds removes cysts from the skin. Visual cues-like colorful posters showing the “5‑step” method-boost recall.

- Food safety: Teaching families to rinse raw produce with clean water, peel when possible, and avoid cross‑contamination lowers the risk of ingesting cysts.

- Sanitation: Simple latrine construction and safe waste disposal prevent cysts from entering water sources.

- Public health campaigns: Radio spots, community theatre, and mobile alerts reinforce messages in local languages.

- School health programs: Integrating parasite‑prevention modules into science or life‑skills classes creates a generation that knows how to protect themselves.

Comparing two popular approaches

| Aspect | School‑Based Curriculum | Community‑Wide Campaign |

|---|---|---|

| Target audience | Students (6‑18y) | All ages, especially adults |

| Delivery method | Classroom lessons, hands‑on demos | Radio, posters, local theatre |

| Cost per capita (2024) | US$0.45 | US$0.32 |

| Behavior change speed | Medium (3‑6months) | Fast (1‑2months) for specific actions |

| Long‑term sustainability | High - curriculum repeats annually | Variable - depends on funding |

The table makes it clear that the best strategy often blends both: schools embed core habits early, while community campaigns reinforce and reach those outside the school system.

Practical steps for teachers, parents, and community leaders

- Start each class with a 2‑minute hand‑washing demo. Use a UV‑reactive gel so kids can see how many germs they missed.

- Provide a simple hand‑washing poster that shows the steps in the local language. Hang it near sinks and latrines.

- Organize a monthly "clean‑water day" where students test local water sources with inexpensive test strips for turbidity and chlorine.

- Teach families a three‑step food‑prep rule: (a) wash, (b) peel or cook, (c) store in covered containers.

- Partner with local health clinics to bring a nurse into the school once a term for a Q&A on parasites.

- Encourage community leaders to broadcast short radio jingles that repeat the hand‑washing message during peak water‑collection times.

When these actions become routine, the community builds an invisible shield that stops cysts before they enter the gut.

Real‑world success stories

In 2021, the city of Gulu, Uganda, launched a combined school‑and‑radio program targeting amoebiasis. Over two years, reported cases fell from 12per1,000 to 4per1,000, a 66% reduction. The key lesson? Consistency. Teachers reinforced the radio messages, and parents reported better household hygiene.

Another example comes from the coastal town of Veracruz, Mexico. A local NGO ran a "Clean Kitchen" workshop series, teaching mothers how to disinfect cutting boards and wash vegetables with chlorine‑based solutions. Within six months, the local clinic saw a 30% drop in diarrheal cases linked to amoeba.

Measuring impact: What metrics matter?

- Incidence rate: Number of new amoeba cases per 1,000 population.

- Hand‑washing compliance: Observed proportion of students washing correctly.

- Water quality scores: Turbidity and chlorine residual readings.

- Knowledge retention: Pre‑ and post‑test scores on parasite facts.

Collecting these numbers every six months lets program managers tweak lessons and allocate resources where they’ll have the biggest impact.

Common pitfalls and how to avoid them

"We taught them once, problem solved" is a myth. Habit formation needs reinforcement. Also, avoid overly technical jargon; a 10‑year‑old should grasp the core idea without a biology degree. Finally, don’t assume that soap is always available-pair education with low‑cost hand‑washing stations (e.g., tippy‑tap systems) to keep the behavior feasible.

Next steps for readers

If you’re a teacher, draft a one‑page hand‑washing cheat sheet and test it on a class tomorrow. If you’re a parent, challenge your family to a week‑long "no‑cyst" challenge where everyone tracks hand‑washing and food‑prep habits. Community leaders can start a dialogue with local health officials about funding a tippy‑tap installation at the nearest school.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can amoeba infections be caught from swimming pools?

Most pools are treated with chlorine, which kills cysts. However, if a pool’s filtration system is malfunctioning or chlorine levels are low, there is a small risk. Regular testing and proper maintenance keep the risk negligible.

Is boiling water enough to kill amoeba cysts?

Yes. Boiling water for at least one minute destroys cysts of Entamoeba histolytica. It’s a reliable method when safe water isn’t available.

How often should schools update their health‑education curriculum?

A review every two to three years works well. Updates should incorporate new data on local water quality, emerging pathogens, and feedback from teachers and students.

What low‑cost tools can help reinforce hand‑washing in remote areas?

The "tippy‑tap"-a foot‑operated water dispenser made from a bucket, rope, and a tap-provides hand‑washing water without plumbing. Pair it with a bar of locally‑made soap for best results.

Are there vaccines against amoeba infections?

No approved vaccine exists yet. Research is ongoing, but for now education and hygiene remain the most effective preventive tools.

Comments(10)