Primaquine Safety Calculator

This tool helps determine safe primaquine dosing based on WHO guidelines. Always confirm G6PD status before prescribing.

Quick Summary

- Primaquine is the only widely available drug that kills dormant malaria parasites (hypnozoites) and infectious gametocytes.

- It enables a "radical cure" for Plasmodium vivax and helps block transmission of Plasmodium falciparum.

- Safety hinges on testing for G6PD deficiency; without it, the drug can cause severe hemolysis.

- World Health Organization (WHO) recommends single‑dose primaquine for falciparum and 14‑day regimens for vivax.

- Newer alternatives like tafenoquine are emerging, but primaquine remains the workhorse in most endemic regions.

When it comes to wiping malaria off the map, Primaquine is a synthetic 8‑aminoquinoline antimalarial that targets liver‑stage parasites and sexual stages in the bloodstream. Its unique ability to clear dormant forms that other drugs miss makes it indispensable for any global eradication plan. Below we unpack how the drug works, why it matters, the safety hurdles, and what the future looks like.

The word primaquine often appears alongside terms like "radical cure" and "transmission blocking," because it is the only medication currently approved for both functions in most malaria‑endemic countries.

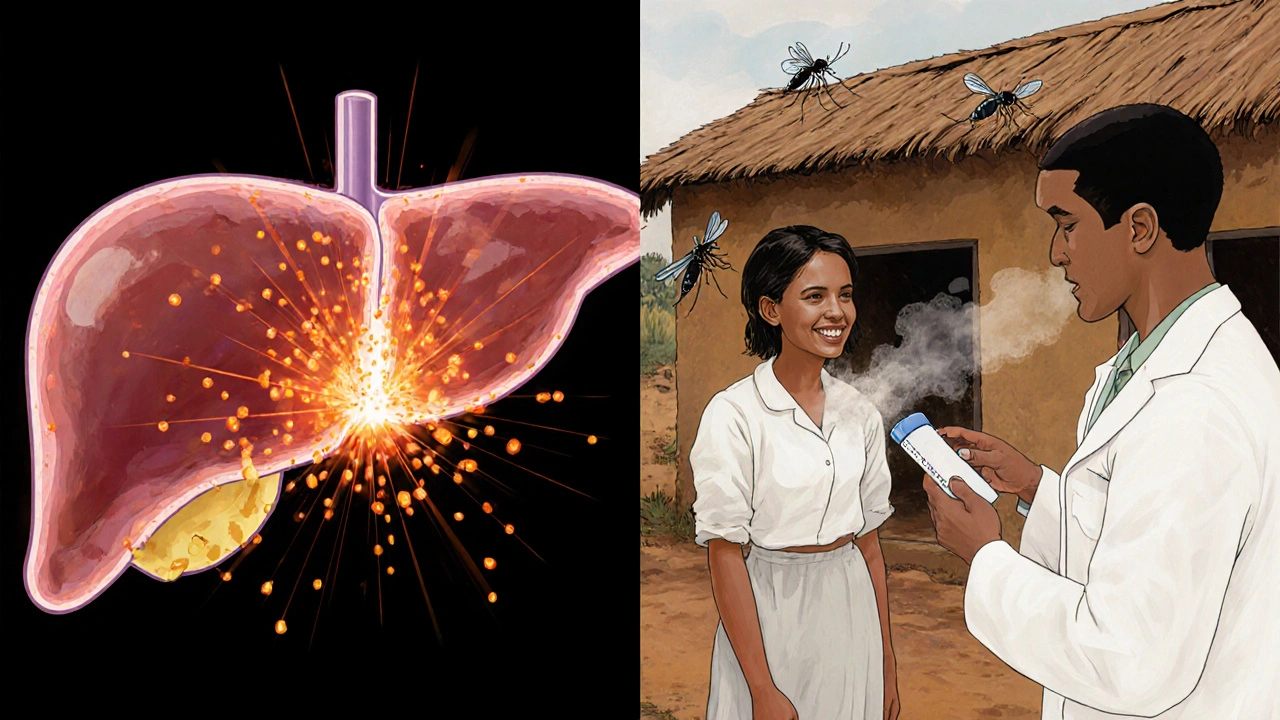

How Primaquine Works Against Malaria

Malaria parasites have a complex life cycle that includes a silent liver stage and a blood stage that causes illness. Two species, Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale, can hide in the liver as hypnozoites for weeks or months, later re‑emerging to cause relapse. Primaquine penetrates liver cells and chemically damages the DNA of these dormant forms, effectively “awakening” and destroying them.

Beyond the liver, primaquine is toxic to mature gametocytes of Plasmodium falciparum. By clearing gametocytes, it stops infected humans from passing the parasite to mosquitoes, cutting the transmission cycle.

These dual actions-eliminating hypnozoites and gametocytes-are why health authorities label primaquine a "radical cure" drug. Without it, even after successful blood‑stage treatment, patients remain reservoirs for future infections.

Why Primaquine Is Essential for Eradicating Malaria

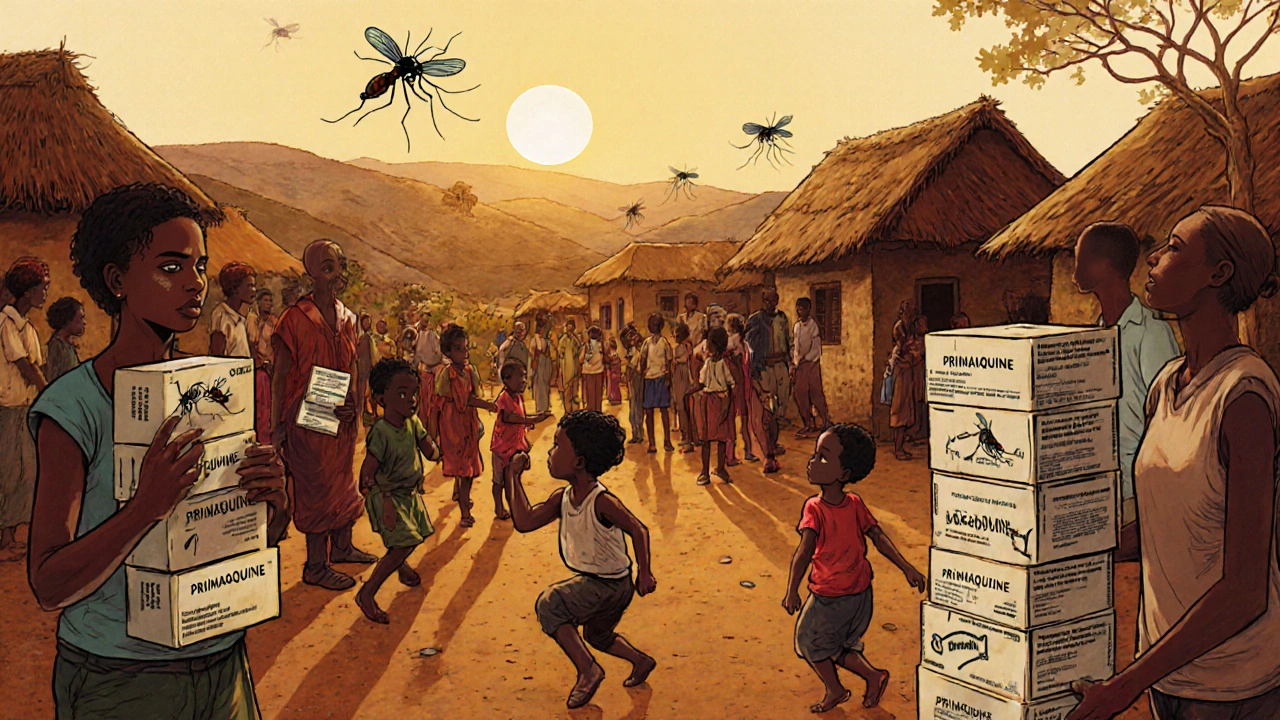

Global eradication targets require two things: clearing the disease from individuals and stopping its spread. Primaquine checks both boxes.

- Relapse prevention: In regions where Plasmodium vivax dominates, up to 80 % of infections are relapses. A 14‑day primaquine course reduces relapse rates to below 5 % when combined with a blood‑stage partner drug.

- Transmission reduction: A single low‑dose primaquine (0.25 mg/kg) given alongside artemisinin‑based combination therapy (ACT) cuts falciparum gametocyte carriage by 90 % within 48 hours.

- Cost‑effectiveness: At an average price of US $0.10 per 15 mg tablet, primaquine is the cheapest drug capable of achieving radical cure, making it affordable for mass‑drug‑administration campaigns.

These benefits translate into measurable public‑health gains. For example, a 2019 trial in the Brazilian Amazon showed a 72 % drop in new vivax cases after implementing weekly primaquine‑plus‑chloroquine therapy across 15 villages.

Safety Concerns: G6PD Deficiency

The biggest hurdle to widespread primaquine use is hemolysis in people with glucose‑6‑phosphate dehydrogenase (G6PD) deficiency. This X‑linked genetic condition reduces the red blood cell’s ability to handle oxidative stress, which primaquine can provoke.

Estimates suggest that 5‑20 % of malaria‑endemic populations carry some form of G6PD deficiency, with higher rates (up to 30 %) in parts of Southeast Asia and the Horn of Africa.

To mitigate risk, WHO recommends:

- Point‑of‑care G6PD testing before any primaquine regimen, especially the 14‑day high‑dose schedule.

- Using the low‑dose single‑shot (0.25 mg/kg) for falciparum transmission blocking, which is safe even in moderate G6PD deficiency.

- Monitoring patients for signs of hemolysis (dark urine, jaundice) for 48 hours after the first dose.

When testing is unavailable, some programmes adopt a “test‑and‑treat” strategy: they give a short 7‑day low‑dose primaquine to all, accepting a small risk of hemolysis because severe outcomes remain rare.

Comparing Primaquine with Other Radical Cure Drugs

| Attribute | Primaquine | Tafenoquine |

|---|---|---|

| Dosing regimen | 14‑day (0.5 mg/kg per day) or single low‑dose (0.25 mg/kg) | Single 300 mg dose (once‑off) |

| Approved for | Radical cure of P. vivax, transmission blocking of P. falciparum | Radical cure of P. vivax (licensed in US, EU) |

| Half‑life | ~6 hours (active metabolites longer) | ~15 days |

| Safety in G6PD deficiency | Risk of hemolysis; requires testing for high‑dose regimen | Higher hemolysis risk; requires quantitative G6PD test |

| Cost per treatment | ~$1‑$2 | ~$20‑$30 |

While tafenoquine offers the convenience of a single dose, its long half‑life means any hemolytic episode is prolonged, and its price remains prohibitive for low‑resource settings. For now, primaquine retains its edge in accessibility and proven field experience.

World Health Organization Guidelines

The WHO’s 2022 Malaria Treatment Guidelines make three clear statements about primaquine:

- For Plasmodium falciparum infections, add a single low‑dose primaquine (0.25 mg/kg) to ACTs to block transmission, unless G6PD testing is unavailable and the risk outweighs benefits.

- For Plasmodium vivax, prescribe a 14‑day regimen (0.5 mg/kg per day) after confirming normal G6PD activity.

- When quantitative G6PD testing is present, high‑dose primaquine (0.75 mg/kg per day) can be used for faster relapse prevention, especially in high‑transmission zones.

These recommendations hinge on the ability of national programs to integrate G6PD testing into routine malaria case management.

Implementing Primaquine at Country Level

Successful deployment requires coordination across three fronts: policy, supply chain, and community engagement.

Policy and Guidelines

Ministries of Health should adopt the latest WHO guidelines, updating national treatment protocols to include primaquine as a mandatory add‑on for falciparum cases and as standard of care for vivax.

Supply Chain Management

Because primaquine tablets are stable at 30 °C for two years, countries can stock them centrally and distribute to peripheral clinics using existing antimalarial logistics networks. However, keeping separate packs for the 14‑day regimen (15 mg tablets) avoids dosing errors.

Training and Community Outreach

Health workers need short refresher courses on G6PD testing, dose calculation, and monitoring for hemolysis. Community health volunteers can educate patients about the importance of completing the full course, especially in remote villages where follow‑up is limited.

Monitoring and Evaluation

Countries should track three key indicators:

- Proportion of malaria cases receiving primaquine as per guideline.

- Incidence of reported hemolysis events linked to primaquine.

- Relapse rates for vivax malaria after program rollout.

Data from the Malaria Atlas Project (MAP) shows that nations incorporating primaquine saw a 45 % faster decline in vivax incidence between 2015 and 2022 compared to those that relied solely on blood‑stage treatment.

Future Directions

Research is still exploring shorter, safer regimens. Trials of a 3‑day high‑dose primaquine schedule (1 mg/kg per day) aim to reduce treatment burden while maintaining efficacy. Meanwhile, point‑of‑care quantitative G6PD tests are becoming cheaper, with some devices now under $2 per test, which could finally eliminate the safety bottleneck.

Another promising avenue is integrating primaquine into seasonal malaria chemoprevention (SMC) packages for children in the Sahel. Early pilot data suggest that adding a single low‑dose primaquine to SMC reduces community gametocyte prevalence by 30 %.

Until newer drugs become widely available and affordable, primaquine will remain the linchpin of any malaria‑eradication strategy.

Frequently Asked Questions

What is the difference between a “radical cure” and ordinary malaria treatment?

Ordinary treatment (like chloroquine or ACT) clears the parasites that cause fever and illness in the blood. A radical cure also eliminates dormant liver forms (hypnozoites) and sexual stages, preventing relapse and transmission.

Can I take primaquine if I don’t know my G6PD status?

The safest approach is to test first. If testing is impossible, the WHO allows a single low‑dose primaquine (0.25 mg/kg) for falciparum cases because the risk of severe hemolysis is low. High‑dose regimens should never be given without confirming normal G6PD activity.

How long does primaquine stay in the body?

The parent drug has a half‑life of about 6 hours, but active metabolites can persist for up to 2 days. This short residence time means side effects appear quickly and resolve once the drug is stopped.

Is primaquine effective against all malaria species?

It works best against Plasmodium vivax and Plasmodium ovale by clearing hypnozoites. For Plasmodium falciparum, a single low dose blocks gametocytes but does not treat blood-stage infection, so it must be paired with an ACT.

What are the main side effects of primaquine?

Common mild effects include nausea, abdominal cramps, and itching. In people with G6PD deficiency, the drug can cause hemolytic anemia, presenting as dark urine, fatigue, and jaundice. Severe cases are rare when proper testing is done.

Bottom line: without primaquine, the world can’t finish the job of wiping out malaria. Its ability to eradicate hidden parasites and stop transmission makes it the only drug that truly fits the definition of a ‘radical cure.’ As testing improves and new formulations appear, primaquine’s role will only get stronger.

Comments(11)