Every year, Americans fill over 6 billion prescriptions. Nearly 93% of them are for generic drugs. That’s no accident. It’s the result of state laws that tell pharmacists when - and when not - to swap a brand-name drug for a cheaper generic version. But here’s the catch: what’s allowed in Texas isn’t legal in Hawaii. One state might require you to say yes before they switch your medication. Another might switch it automatically and just send you a notice afterward. And if you live near a state border? You might get different rules depending on which pharmacy you walk into.

Why Do These Laws Even Exist?

The goal is simple: save money without risking health. Generic drugs cost up to 80% less than brand-name versions. Since 2009, they’ve saved the U.S. healthcare system over $1.7 trillion. That’s billions in savings for patients, insurers, and Medicaid programs. But not all drugs are created equal. Some, like warfarin or levothyroxine, have what’s called a narrow therapeutic index - meaning the difference between a dose that works and one that causes harm is tiny. Even small changes in how the drug is absorbed can lead to serious side effects. So states had to figure out: how do we encourage savings without putting people at risk?How States Decide: The Four Big Rules

Each state’s law is built around four key decisions. These aren’t suggestions. They’re legal requirements pharmacists must follow - or risk losing their license.- Do pharmacists have to substitute? In 22 states, they must. If the prescription doesn’t say "dispense as written," the pharmacist is legally required to give the generic. In the other 28 states and D.C., substitution is optional. The pharmacist can choose to give the brand name even if a generic is available.

- Do patients have to agree? Thirty-two states use presumed consent. That means the pharmacist can switch the drug unless the patient says no. Eighteen states require explicit consent. The patient must actively say, "Yes, give me the generic," before the switch happens.

- Do patients get notified? Forty-one states require the pharmacist to inform the patient after the switch - usually on the label or via a printed notice. That’s not just good practice. It’s the law.

- Who’s liable if something goes wrong? In 37 states, pharmacists are protected from lawsuits if they follow the state’s rules exactly. But in the other 13? They could be held responsible even if they did everything right.

What About Biosimilars? It’s Even Messier

Biosimilars are the next wave of generics - but they’re not simple copies. They’re made from living cells, not chemicals. The FDA says they’re safe and effective, but states have been slow to catch up. As of 2023, 49 states and D.C. have laws for biosimilar substitution. Hawaii is the outlier: even for biosimilars, they require both the doctor and the patient to give written permission before switching, especially for drugs used to treat epilepsy. States like Florida now require pharmacies to create internal formularies that prove a biosimilar won’t harm patients. Iowa tells pharmacists to stick strictly to the FDA’s Orange Book - the official list of approved generic equivalents. But here’s the problem: the Orange Book doesn’t yet have full ratings for every biosimilar. So pharmacists are left guessing - and that’s not okay when someone’s life depends on it.

The Real-World Confusion

Pharmacists aren’t just filling prescriptions. They’re playing regulatory whack-a-mole. On average, they spend 12.7 minutes per prescription checking state laws, FDA ratings, and patient history. That’s time they could spend counseling patients. Chain pharmacies with locations in multiple states rely on software that auto-checks rules - and even then, 18.3% of prescriptions cross state lines, triggering manual reviews. Patients notice the inconsistency. One Reddit user from New York said: "I have to ask every single person if they want the generic. My friend in New Jersey says the pharmacist just switches it and hands her the bottle. She gets confused when she visits me - why does it work differently here?" That confusion isn’t just annoying. It leads to mistrust. If someone’s thyroid medication suddenly changes and they feel off, they might blame the pharmacist - not the state law that allowed the switch.Who Gets Hurt? The NTI Drug Problem

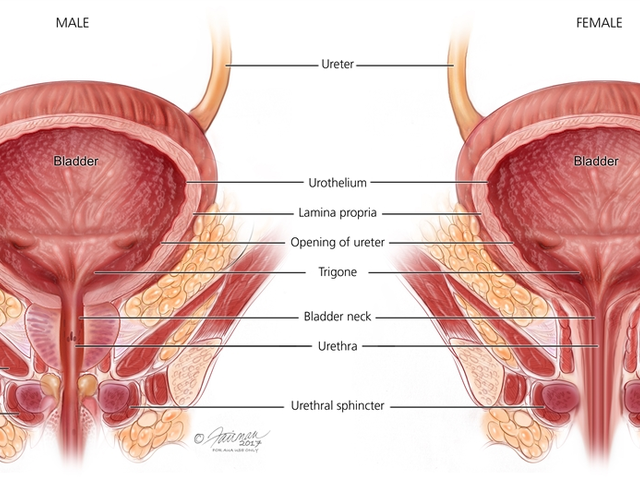

Narrow therapeutic index drugs are the elephant in the room. These include:- Warfarin (blood thinner)

- Levothyroxine (thyroid hormone)

- Phenytoin and carbamazepine (anti-seizure meds)

- Digitalis glycosides (heart medication)

What’s Changing? And What’s Next?

The system is cracking under its own weight. Pharmacists are tired of juggling 50 different rulebooks. Pharmacy schools now teach 45 to 60 hours on state substitution laws - and 92% of states test it on licensing exams. Still, 78% of pharmacists say they’re confused when filling prescriptions from other states. In 2023, the Uniform Law Commission released a draft model law to standardize biosimilar substitution across states. It’s a step toward sanity. Meanwhile, the FDA added 17 new therapeutic equivalence ratings for biosimilars in its 2023 Orange Book update. Twenty-three states are now reviewing their laws to match. The economic pressure is real. States with mandatory substitution laws see 94.1% generic fill rates. States without? Only 88.3%. That’s a $1.2 billion annual savings for Medicaid programs alone, according to Harvard researchers. But the Congressional Budget Office estimates that full standardization could save an extra $8.7 billion by 2028. The question isn’t whether we should use generics. It’s whether we should let 50 different rulebooks decide how and when we use them.What You Can Do

If you’re a patient:- Always ask: "Is this a generic?" and "Was this switched?"

- If you feel different after a switch - especially with thyroid, heart, or seizure meds - tell your doctor immediately.

- Ask your doctor to write "dispense as written" on your prescription if you’ve had problems before.

- Keep a list of your medications and what version you take - brand or generic.

- Use your pharmacy’s software to auto-check state rules - but double-check when prescriptions come from out of state.

- Document every patient refusal, even if you think they’ll change their mind.

- Know your state’s NTI drug list. If you’re unsure, err on the side of caution.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can a pharmacist refuse to substitute a generic drug even if the law allows it?

Yes. In 28 states and D.C., substitution is permissive, not mandatory. Pharmacists can choose to dispense the brand-name drug even if a generic is available and no restrictions are listed on the prescription. Some pharmacists do this if they believe the patient has had a bad reaction to a generic in the past, or if the patient specifically requests the brand.

What does "dispense as written" mean on a prescription?

It means the prescriber is instructing the pharmacist not to substitute the brand-name drug with a generic version - even if one is available and legally allowed. This is often used for narrow therapeutic index drugs or if the patient has had issues with generics before. If this phrase is on the prescription, the pharmacist must follow it, regardless of state law.

Are generic drugs really the same as brand-name drugs?

For most drugs, yes. The FDA requires generics to have the same active ingredient, strength, dosage form, and route of administration as the brand. They must also be absorbed into the body at the same rate and to the same extent. But for drugs with a narrow therapeutic index - like warfarin or levothyroxine - even tiny differences in absorption can affect how well they work or cause side effects. That’s why some patients and doctors prefer to stick with one version.

Why do some states require patient consent while others don’t?

It comes down to how each state balances cost savings with patient autonomy. States with explicit consent laws believe patients should have a direct say in what they take, especially for critical medications. States with presumed consent assume patients want the cheaper option unless they object - which increases substitution rates and lowers costs. There’s no national standard, so it’s left to each state legislature to decide based on local priorities.

Can I get in trouble if I switch back and forth between brand and generic?

You won’t get in legal trouble, but switching between versions - especially for NTI drugs - can be dangerous. Your body adjusts to a specific formulation. If you alternate between generics from different manufacturers or between brand and generic, your drug levels can fluctuate, leading to under- or over-treatment. Doctors often recommend sticking with one version for consistency. If you’re unsure, ask your pharmacist or prescriber to help you pick one and stick with it.

Comments(14)